2023 Articles:

The correct spelling and status of the types of Sabal yapa (Arecaceae) are updated. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21414/B1RG6K

The collection C. Wright 3219 is mixed, and here I resolve this conundrum by separating it into two species: Thrinax radiata and Coccothrinax martii. In addition to their identification, I report the type category and herbaria where specimens are deposited. I report the same for the C. Wright 2329 and C. Wright 3218 collections. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21414/B1W88H

The tree Aphananthe aspera (Cannabaceae) at the Los Angeles County Arboretum & Botanic Garden in Arcadia, California is neotypified, illustrated, and discussed, including its history, taxonomy and nomenclature, a description, and growth performance at the site. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21414/B1101B

The nomenclature and typification of Sabal yapa (Arecaceae) are corrected and updated. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21414/B14S3Z

Chrysalidocarpus blackii, a new species here named described from a cultivated plant, is discussed, illustrated, compared to similar species, and its growth performance assessed in the subtropical, Mediterranean climate of southern California. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21414/B18G67

Leaf removal on Plumeria rubra (Apocynaceae) is a common horticultural practice. However, preliminary data from our study suggest that leaf removal could be responsible for more shoot tip and shoot lateral decay in the cultivars ‘Hollywood Pink’, ‘Nebel’s Rainbow’ #1, and ‘Pink Cloud’ than simply allowing the leaves to remain on the shoot until they fall away naturally. Stripping or cutting the leaves off without allowing them to fall away naturally can cause wounds on the shoots, which can facilitate entry of decay-causing primary and secondary pathogens. Also, when leaves are retained on the shoot, they might offer protection against early and mid-winter shoot cold damage; thus, shoots devoid of leaves might be more susceptible to cold damage. Cold damage itself can lead to entry of primary or secondary pathogens. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21414/B1D59H

Charles Wright's collections have made a significant contribution to Cuban palms (Arecaceae), including Euterpe and Prestoea. Until now Oreodoxa manaele Mart. was considered a basionym of Euterpe manaele Griseb. & H. Wendl. ex Griseb. Here I show that both names are heterotypic synonyms of Prestoea acuminata var. montana. Also, the species of Prestoea that Plumier saw on his trip to the West Indies in the 17th century is updated. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21414/B1J010

The aim of this study is to examine the historical record behind the current presence of the date palm (Phoenix dactylifera, Arecaceae) and other exotic orchard fruits in the Big Bend area of Texas and, in the case of the date palm, to attempt to determine how it disseminated and naturalized. We confirm that date palms in Big Bend area are at five locations in the National Park, one in the State Park, and two near the parks. As stated, the exact historic time period, origin and place of the date palms’ introduction are unknown. It is without question that the Spanish missions promoted fruit tree orchards in their early settlements. The first successful introduction of dates to Big Bend likely took place in the early to middle 1800s; earlier attempts may well have failed before Klee reported date palms in Big Bend in 1882. Agricultural settlers along the Rio Grande and at inland ranch sites cultivated a few fruit crops; the only physical evidence today are the date, peach, fig, and pecan trees at a few ranch sites, an historic report of a pear tree at Hot Springs Village, and citrus and grapes from the Crawford-Smith Ranch in the present State Park. Of the orchard crops documented to have been introduced in Big Bend—citrus, date, fig, grape, pecan, peach, pear— only grapes and pecans are now commercial crops in the Trans-Pecos Region. Meanwhile, the date palm has become naturalized, reproducing from seed and offshoots in the presence of ground water. The two date palm clusters at Hot Springs Village are the best example. The most plausible way dates spontaneously established themselves from seed in the protected areas is by human action, as exemplified in Fresno, Cattail, and Mule Ear’s canyons in the national park and in the state park in Lower Shutup Canyon. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21414/B1NP4Z

We conducted a replicated study on the effect of leaf removal on shoot decay in two cultivars of Plumeria rubra (Arecaceae), 'Hollywood Pink' and 'Nebel's Rainbow'. Overall, across both cultivars, treatment differences were nearly significant for shoot decay, with stripping of leaves having the largest mean extent of shoot decay followed by cutting off leaves and not removing leaves (9.2 vs. 4.7 vs. 2.8 cm, respectively, P< 0.1). This study suggests that the practice of leaf removal, especially stripping off leaves, might be responsible for more shoot decay than simply allowing the leaves to remain on the shoot until they fall away naturally. Removal of leaves prematurely, either by cutting or especially stripping them off, can cause wounds on the shoots, which can facilitate entry of decay-causing primary and secondary pathogens. If leaf removal is implemented, leaves should be cut off, not stripped, and removal should be done in early fall to allow petiole scars to cover over prior to the onset of cool, wet weather, the latter of which can enhance pathogen entry and decay initiation and development. For cultivars that tend to retain leaves naturally through the winter, consider leaf removal in spring before new growth emerges and when warmer, drier conditions prevail, which can reduce pathogen entry and decay initiation and development. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21414/B1SG6W

In new genus and species records for two Cuban palms (Arecaceae), Copernicia hospita is documented in the Alturas de Sancti Spíritus and Massif of Guamuhaya and C. yarey is documented at La Mensura in the Mensura-Pilotos National Park in the Sierra de Nipe, Cuba. The maximum elevation where Copernicia occurs in Cuba is reported. The distribution of both species in Cuba, including municipalities for the provinces of Sancti Spíritus and Holguín, is discussed. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21414/B1X595

The correct citations for five of the most significant 19th-century personages (Grisebach, Richard, Sagra, Sauvalle, and Wright) in the Flora of Cuba are provided. New taxa that Achilles Richard named and described in Sagra should be “A. Richard.” The correct years of publication for new taxa named and described in Grisebach's Flora of the British West Indian Islands are 1859, 1860a, 1860b, 1861a, 1862, and 1864; in his Plantae Wrightianae, e Cuba Orientali the correct years are 1861b and 1863; and in his Catalogus Plantarum Cubensium the correct years is 1866. The correct and accepted authorship citation for the new taxa that Charles Wright named and described in Sauvalle should be “C. Wright,” while those that appear again in the reprinted book in 1873 are later isonyms. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21414/B1201N

Healthy urban forests provide a suite of ecosystem services and amenities to cities and residents. Urban forest health can be monitored through field techniques, such as SPAD meter chlorophyll measurements, spectral reflectance values from satellite imagery, and imagery from Google Maps Street View. Satellite imagery and Google Maps Street View (GMSV) allow access to historical and relatively recent conditions. This paper evaluates all three of these sources for detecting decline in a set of Ficus microcarpa street trees in Lakewood, California, U. S. A. A planting of 25 Ficus microcarpa street trees was assessed in three phases: field observations and SPAD measurement; subjective health and canopy density ratings based on historical Google Maps Street View images; and spectral reflectance values in four bands from Worldview-II satellite data collected in 2010, 2012, 2016, and 2018. Data from each of 28 input variables were analyzed for correlation. Generally, five categories of strong variable pair relationships existed: (1) Field/GMSV Relationship, (2) GMSV/Satellite Relationship, (3) Consistency Over Time, (4) Observation Self-Consistency, and (5) Satellite Self-Consistency. The strongest correlations were between adjacent bands of reflectance collected in the same year (|r| ~ 1 to 0.85) and between subjectively rated health and canopy density ratings (r ~ 0.91 to 0.82). There was a significant difference in the Near-Infrared reflectance values between the trees with and without a history of recent root pruning (p < 0.06 and p < 0.05). DOI: https://doi.org/10.21414/B15P4M

Grafting is not a propagation method one commonly associates with plumerias, which grow easily, simply, and less expensively from cuttings. However, grafting plumerias offers some advantages over cuttings. Here we discuss the principles and practices of grafting and then outline and illustrate a splice grafting method used in southern California for Plumeria rubra. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21414/B19G6J

Here I correct some errors with my previous work on the nomenclature of Copernicia glabrescens and C. macroglossa (Arecaceae). DOI: https://doi.org/10.21414/B1F59T

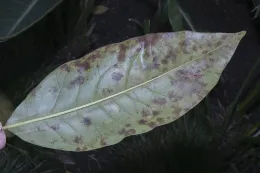

Powdery mildew caused by the fungus Erysiphe magnifica is documented and confirmed on Magnolia grandiflora landscape trees for the first time. Here we provide an account of this novel pathogen/host interaction, including information about the pathogen, its relatives, host Magnolia species, and their ranges; symptoms and signs on M. grandiflora; and landscape management. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21414/B1K019

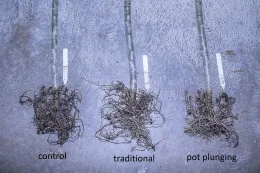

Pot plunging when planting plumerias in the ground (where the plant is not removed from the pot when planting) is done for a number of reasons, one of which is that it purportedly results in more root and above-ground growth. In a preliminary study using Plumeria rubra, we substituted larger containers for the ground and randomly assigned six plants each to three treatments: 1. Traditional planting where the plant is removed from the nursery pot prior to planting; 2. Pot plunging; and 3. Control, plant remained in the nursery pot. After one year all 18 plants were measured for stem height and diameter, quantity of leaves, and root dry weight. Traditional planting produced significantly more stem height and diameter and quantity of new leaves than pot plunging or the control Treatments did not significantly affect root dry weight. Traditional replanting appears to be the preferred method for encouraging plant growth. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21414/B1PP48

In late June, 2023, we observed severe and extensive chlorophyll photobleaching (CPB) on the landscape tree Ficus benjamina in coastal Southern California from San Diego to Santa Barbara. We surveyed 258 trees along three 16.1- to 19.9-km transects from near the ocean to inland in Los Angeles and Orange Counties. We recorded the location, severity of CPB, height and width of trees, and whether they had been pruned in the previous nine months. Analyses of these data showed that trees closer to the ocean, recently pruned, and/or taller showed significantly more CPB. We suggest that a combination of environmental factors or stresses, many related to the unprecedented long, cool, and wet winter, and cultivation practices, such as pruning, likely triggered CPB. To prevent and/or mitigate future occurrences of CPB, we suggest providing optimal cultivation (water, fertilizer, mulch) and avoid pruning from July through February. DOI: https://doi.org/10.21414/B1TG66

Here, I provide a detailed, well illustrated account of Areca novohibernica (A. guppyana) (Arecaceae), including its history, taxonomy and nomenclature, a description, distribution and ecology, conservation, miscellaneous notes, and cultivation. Doi: https://doi.org/10.21414/B1Z59G