(Editor's Note: Forest entomologist Malcolm Furniss of Moscow, Idaho, researched the life of noted scientific illustrator Mary Foley Benson, 1905-1992. In her later years, she served as an illustrator for the UC Davis Department of Entomology.)

By Malcolm M. Furniss

Moscow, Idaho

MalFurniss@turbonet.com

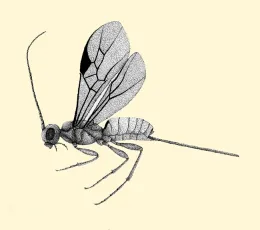

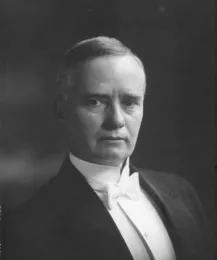

My introduction to the work of scientific illustrator Mary Foley Benson (1905–1992) was happenstance. I am a forest entomologist, engaged for many years in research on bark beetles and associated organisms, including parasitoid Hymenoptera. Since 1963, I have resided in Moscow, Idaho, and have had ties with the former Bureau of Entomology laboratory at Coeur d'Alene, 90 miles to the north. There, Donald De Leon had studied Coeloides dendroctoni Cushman, a braconid preying on larvae of a scolytine, Dendroctonus ponderosae Hopkins, in western white pine. While reading his publication on the braconid's biology, I admired the drawing of a female wasp credited to Mary Foley (Fig. 1). A colleague noted my curiosity about this artist and called my attention to a photo of her in 1926 at age 21 (Fig. 2), when she was employed as a scientific illustrator with USDA. Subsequent inquiry led to discovering Mary's connections to entomology, including close acquaintance of the renowned Smithsonian Diptera taxonomist, John Merton Aldrich (1866–1934) (Fig. 3). I share here an account of Mary's life, concluding with her finding fulfillment and support in the community of Davis, Calif.

Mary Carilla Foley was born on April 2, 1905 at Storm Lake, Buena Vista County, Iowa, to Guy William Foley and Cora Helen Walrod. She had a brother, Charles, who had a flying service at Roosevelt Field, Long Island, and who had a pivotal role in her early adult life. Mary's inherent artistic talent became apparent while in first grade when her drawing of a puppy drew praise from her teacher (Wellings 1992). From then on, Mary made art her life and never forgot that teacher's encouragement.

At age 17, she left her Midwest roots to live with close family friends, John Aldrich and his wife, Della, in Washington, DC. Her intent was to go to art school—until then, she had been largely self-taught—but first, she had to earn tuition money. “Uncle Merton,” as she fondly referred to Aldrich, got her a job as an entomological draftsman with the USDA Bureau of Entomology. She learned quickly and eventually became Chief Scientific Illustrator. In evenings, she took art classes, graduating from the National School of Fine and Applied Arts and later attended the Corcoran School of Art. The closeness of Mary and Aldrich was like father and daughter. The tragic loss of his young son (Furniss 2010) may have affected his feelings for Mary, who would not have been much older.

Road Trip West with John and Della Aldrich, 1927

Mary and the Aldriches departed Washington on May 29, 1927 (nine days after Lindberg's Atlantic flight) in their Chevrolet (Fig. 4) coach loaded down with camping gear and headed across the continent on an adventure of their own. Aldrich kept a meticulous, detailed diary. A typed copy was discovered at the University of Idaho, Department of Entomology after his death and published by Paul Arnaud Jr. (Aldrich 2001). References to Mary appear throughout the diary and provide rare personal recollections of her. Her relatives and her closest friend, Margaret Hoyt, had passed away prior to my interest in her biography.

Driving was shared; however, it became apparent that Mary liked to drive and John often complimented her skill, so she drove the most. Two days into the trip, Aldrich noted: “Mary made fast time, keeping around 45.” Mary had little opportunity to paint until they reached the Rocky Mountains and a place named Wagon Tongue where Aldrich began collecting flies. Here she made water color paintings of a flower (Doedecatheon) and others not identified. Later, near Wells, Nevada, John packed up two Schmitt boxes pinned so far on the trip and mailed them with several small boxes of unmounted flies to Washington: “… some thousands of Diptera to be worked over later at home. Some good things there, I know.”

Eventually, they reached California and entered Yosemite National Park via Tioga Pass on July 4, having to drive over a patch of remnant snow. Nearing Bridal Veil, they came to a bear beside the road being fed by others. Mary stepped forward to get in a photo, but the bear was in the shade. Aldrich asked her to move the bear into the sun. As she came close to him, he gave her a bite above the knee; however, it only roughened the skin. Afterward, they made light of the episode.

Mary departed at Portland by train to return to her job. As John and Della drove up the scenic Columbia River highway heading for Moscow, they reminisced about her and missed having her company; they wished that she could be there at every turn. After thousands of miles cramped together, she had, indeed, become family!

John Aldrich had met and married Della Smith in Moscow after the untimely death of his first wife, Ellen Roe, and infant son, Spencer. The Aldriches were in Moscow from July 19 to Aug. 4, 1927, visiting Della's relatives and some of his acquaintances from his time at the University of Idaho, 1893–1913. On Sept. 2, the travelers reached home after being gone since 29 May. Aldrich died seven years later while completing plans to start early in June on another of his biennial collecting trips to the Pacific Coast. He was buried beside Ellen and son Spencer in the cemetery at Moscow.

Aviatrix Years

Mary's job at the Bureau of Entomology included painting insect-damaged crop plants such as appeared in the 1952 Yearbook of Agriculture (USDA 1952). Perhaps to break the boredom, she painted a parade of striped cucumber beetles across the office wall. Her boss was not amused (Wellings 1992). That phase of her life changed with marriage to Russell Benson, a patent lawyer and engineer with the US Patent Office, in 1928 and birth of a son, John, in 1931. In a Washington Post interview (Lewis 1937), she seemed to be living a normal life of a woman of the time “… keeping a home for her husband and small son, doing most of the cooking and making most of her own clothes.” They had designed their house in Georgian Colonial style with a studio for her painting. During the previous summer, she had laid a flagstone terrace while Russell built an outdoor fireplace. However, their relationship was less tranquil than it was portrayed.

Four years after her marriage, Mary had been given her first airplane ride by her brother, Charles, who had charge of one of the hangars at Roosevelt Field, Long Island (from where Lindberg had taken off on his Atlantic flight in 1927). That experience led to her taking flying lessons at the College Park, MD airport two or three times per week until receiving her pilot's license. Interviewed in later years, she divulged that she had kept her flying lessons secret from Russell (Wellings 1992). The marriage had become stressful and she found flying to be a great outlet from her exacting art work and her difficulties at home: “When I was flying, I left all my trouble on the ground. There was nobody up there but God and me.”

When Mary soloed in 1937, Charles gave her a J-2 Cub (Fig. 5). Her spirited nature showed in her flying: “I used to have such fun with it. Before I would land, I would wind it up with three giant loops in a row before they told me not to [not designed for aerobatics] (Haag 1983).” Owning an airplane expanded her involvement with flying. She became active in aviation organizations, including membership in The Ninety-Nines, an international organization for licensed women pilots founded by Amelia Earhart. She also joined the Washington Air Derby Association and placed second in her first air race, at College Park in May 1939 (Lewis 1937).

As World War II loomed, Mary's marriage was ending. Her son was in boarding school, so she joined Charles at his aviation business at Roosevelt Field, studied radio and navigation, became a member of the Civil Air Patrol and began ferrying airplanes for the War Training Service (Wellings 1992). She did not speak of her ferrying experiences except for saying that townsfolk came to see the woman flier after she was forced to land in a farm pasture and was waiting for a new propeller. She enlisted in the Women's Army Corps on Sept. 9, 1943 and instructed navigation to bomber crews in an on-ground Link Celestial Navigation Trainer. She regretted that women pilots were not allowed then to teach in the air.

When war ended, Mary relocated to Los Angeles where she attended Otis College of Art and Design from 1948–1951. Her training included instruction from Norman Rockwell, who spent the winter months there as artist-in-residence: “He was a wonderful person, with a fine sense of humor, and a scientific illustrator as well as a historian” (Tracy 1977). Afterward, she was a free-lance illustrator at Benson Studios. However, she did not attract the attention of newspaper reporters the way she had at Washington.

Home at Last … Davis

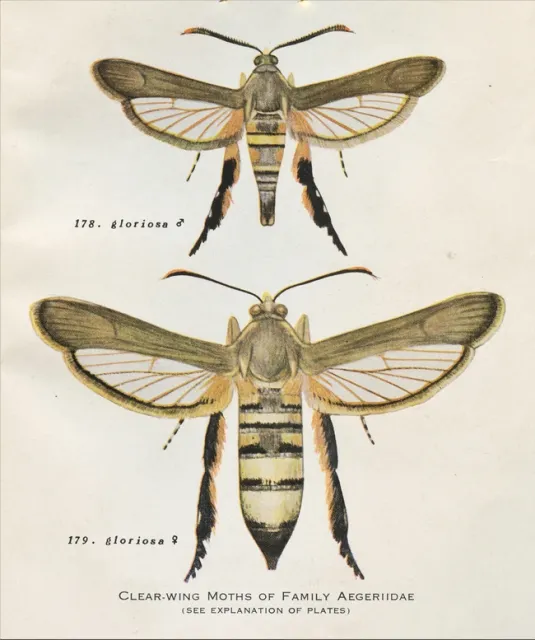

A great change came in 1964, when she was hired by Howard McKenzie at the University of California, Davis, as an illustrator for his monumental book on mealybugs (McKenzie 1967). She must have impressed him with her renditions of clearwing moths in Bulletin 190 of the U.S. National Museum (Engelhardt 1946) (Fig. 6). That publication contains 167 of her watercolor paintings of adult male and female clearwing moths and 87 line drawings of their genitalia. The paintings are eye-catching. When my nephew, Sean Furniss, saw them among the Engelhardt holdings at the Smithsonian, he was impressed with how real they appeared. I marvel that anyone could capture such natural colors by mixing pigment and rendering such life-like images with a brush.

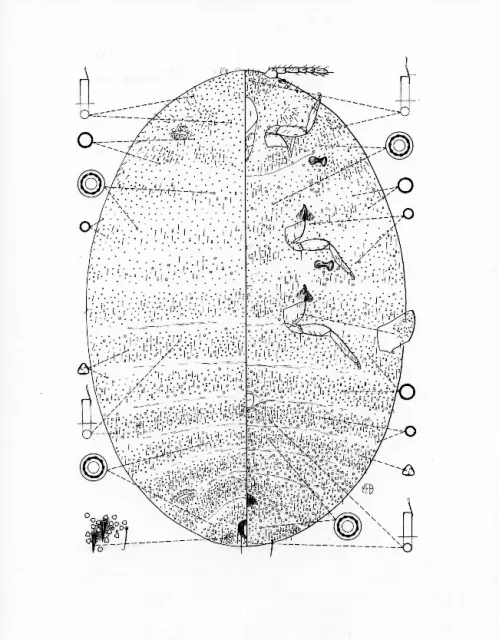

Mary painted and drew mealybug illustrations for Howard McKenzie until his death in 1968. His 526-page treatise of California species has interspersed among its pages 21 of her watercolor paintings of species in their plant habitats (Fig. 7). The book also includes many of her line drawings of microscope slides of holotype adult females, split longitudinally by dorsal and ventral views (Fig. 8). The drawings include minute detail only seen by microscope at high magnification. Mary had become skilled in microscopy and, although not formally trained in entomology, she had to have learned much technical detail about what she was asked to draw. After McKenzie died, Douglass Miller completed two joint manuscripts containing illustrations by Mary (Miller and McKenzie 1971, 1973). Earlier, she had illustrated mealybugs in the monograph on the genus Asterolecanium by Russell (1941).

Announcement of publication of McKenzie's book noted that it had been illustrated by Mary and included her pedigree dating to her employment with USDA Bureau of Entomology in Washington DC during 1922-1928 as Chief Scientific Illustrator. Her presence in the community had already become known by her participation in Chamber of Commerce events, teaching painting techniques through the Davis adult education program and scientific illustration through the University of California Cooperative Extension.

In the years after McKenzie's death, she contracted a painting project for Harry Lange to illustrate a book on insects infesting California crops. The idea was to show both the insect and its host plant in realistic fashion. However, when Mary portrayed the plant, the accompanying insect was at the same scale, much too little to suit entomologist Lange. His wife, Ellen Lange, recalls that, “A real problem with depicting insects and plants is the difference in size. Harry Lange used to have battles with Mary about the plants being too big, i.e., emphasis on the plants versus the insects.” They resolved the problem by superimposing a “magnifying glass” to enlarge the insect (Fig. 9). The proposed publication never materialized; her 55 paintings are stored in the Bohart Museum of Entomology at Davis. In looking back, such paintings (and to some extent, drawings) were being replaced by digital photography and scanning electron microscopy.

Having retired from the Department of Entomology work, Mary (Fig. 10) said: “For the first time in my life, I can paint what I feel like painting most. I have always wanted to paint wildflowers, especially California wildflowers.” (Barr, 1992). She set about doing just that and put her paintings on display for sale at public places, gradually developing a devoted following. “This is the greatest place in the world for me. I get such support from the people of Davis. They hang my work all over town.” (Haag 1983).

An event in 1983 crowned her rise to prominence beyond the Davis community. At the Smithsonian's invitation, 45 of her paintings were displayed there during May-June, entitled, “Paintings of California Flora.” In her letter of Nov. 20, 1982 to Officer of Exhibits, William Haase, she listed the paintings, some of which included insects, that were to be sent and suggested the name California Flora for the exhibit. She singled out two of the paintings that merited special attention: “The Golden Lupine (Fig. 11) which grows around Davis, along the railroad track. It is almost extinct in the wild. There is some talk of making it the Davis city flower.” (She subsequently donated the original watercolor painting to the city.) And, “The second painting is the California poppy and wild oats. I had hoped to give it to our First Lady, Nancy Reagan, but could not decide just how to go about it. It seemed appropriate since the poppy is our state flower.” The letter concluded with a question regarding who should print the brochure for the show and that the paintings would be shipped by truck. She requested that, after the show, they should be sent to her residence at 1408 Claremont Drive, Davis. No one whom I contacted knew of the fate of these paintings. However, she evidently had prints made of some for sale. I noted one of her paintings being resold by Valley Auction on the Internet; it was number 123 of 500, entitled, “Indian Paint Brush and Fiddleback,” gathered from a vacant lot near her home. It portrays her eloquent, simplistic style that is so appealing to me.

Her dream of a Smithsonian exhibit having come true was timely. Her eyesight began failing soon after. She kept on painting but results were more abstract. During those challenging final years, she kept a positive outlook. As recalled in her obituary (Barr 1982) she said, “Life is like a stream; if you reach a stone you go around it. So now, I'm moving on after the stone.” Mary died at Davis on 18 June 1992 at age 87.

Acknowledgments

Sandra Kegley, Coeur d'Alene, ID, provided Fig. 2, which identified Mary and thereby initiated my interest in pursuing this article. Sean and Martha Furniss, Reston, VA, provided newspaper articles and searched the Smithsonian archives for information about Mary. Ellen Lange, Davis, CA, provided personal recollections of Mary and of her paintings for Harry Lange. Lynn Kimsey, Bohart Museum of Entomology, University of California, Davis, provided obituaries of Mary and a listing of Mary's paintings stored there. Amy Thompson, Special Collections and Archives Library, University of Idaho, provided the photo of Aldrich. Luc Leblanc, W.F. Barr Entomological Museum, University of Idaho, loaned references concerning Aldrich and Mary from the museum library. The manuscript was reviewed by Sandra Kegley, Ellen Lange, Linwood Laughy, and Douglass R. Miller, Systematic Entomology Laboratory, USDA, Beltsville, MD.

Literature Cited

Aldrich, J. M. 2001. Diary of a Western Trip, 1927. Myia - A publication on entomology 6:235-301. California Academy of Sciences.

Barr, P. 1992. Prominent Davis Artist Dies. Davis Enterprise. June 22.

De Leon, D. 1934. The Morphology of Coeloides dendroctoni Cushman (Hymenoptera: Braconidae). Journal New York Entomological Society. XLII: 297-317.

Engelhardt, G. P. 1946. The North American Clear-Wing Moths of the Family Aegeriidae. Bulletin 90. U. S. National Museum. 222 pp.

Furniss, M. M. 2010. John Merton Aldrich (1866-1934) – A Forest Entomologist's View of Idaho's Renowned Fly Taxonomist. Latah Legacy 38:18-23.

Haag, J. 1983. A Californian's Floral Fantasy. The Sacramento Bee. July 24.

Lewis, R. 1937. Vocation and Avocation Combined by D. C. Artist. The Washington Post. October 17.

McKenzie, H. L. 1967. Mealybugs of California with Taxonomy, Biology and Control of North American Species (Homoptera: Coccoidea: Pseudococcidae). University of California Press, Berkeley. 525 pp.

Miller D. R., and H. L. McKenzie. 1971. Sixth Taxonomic Study of North American Mealybugs with Additional Species from South America. Hilgardia. 40:565-602.

Miller, D. R., and H. L. McKenzie, 1973. Seventh Taxonomic Study of North American Mealybugs (Homoptera: Coccoidea: Pseudococcidae). Hilgardia 41: 489-542.

Russell, L. M. 1941. A Classification of the Scale Insect Genus Asterolecanium. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Miscellaneous Publications 424: 1-319

Tracy R. L. 1977. Mary Foley Benson. Her Wildflower Paintings Are “Expression of Gratitude” The Sacramento Bee. August 20, 1977.

USDA 1952. The Yearbook of Agriculture. U.S. Government Printing Office.

Wellings, M. 1992. Davis Has Lost a Free Spirit. The Davis Enterprise. June 23.