Kimsey, now director of the Bohart Museum of Entomology and a UC Davis distinguished professor of entomology, grew up as “Lynn Siri” of El Cerrito, the daughter of a biologist and a biophysicist.

“I always wanted to be a scientist but I really wanted to be a marine biologist then,” she recalled.

Influenced by Jacques Cousteau, and encouraged by her high school biology teacher, she set out on a project that's now being lauded for its legacy data documentation of the Bay's intertidal invertebrates, especially invasive species.

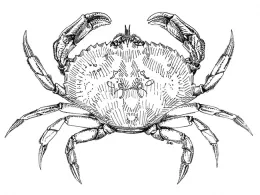

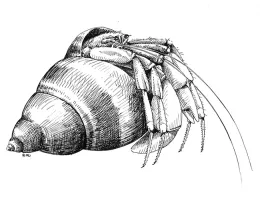

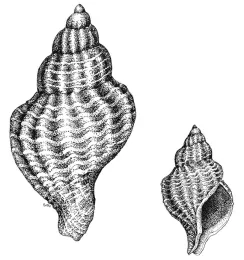

Over a 13-month period, from April 1970 to May 1971, Lynn collected, recorded and sketched 139 marine specimens in the San Francisco Bay, covering 34 locations in six counties, Alameda, Contra Costa, San Francisco, San Mateo, San Francisco and Solano.

She was a high school junior and her work was never published—until now.

Kimsey and marine biologist James Carlton co-authored the article, “The First Extensive Survey (1970–1971) of Intertidal Invertebrates of San Francisco Bay, California,“ published last December in the journal Bioinvasions Records.

The abstract:

“There have been few surveys of intertidal invertebrates in San Francisco Bay, California, USA. Most prior intertidal surveys were limited spatially or taxonomically. This survey of the intertidal invertebrates of San Francisco Bay was conducted over 13 months between 1970 and 1971, generating what is now a legacy data set of invertebrate diversity. Specimens were hand collected at land access points at 34 sites around the Bay. In all 139 living species in 9 phyla were collected; 28.8% were introduced species, primarily from the Atlantic Ocean (62.5%) and the Northwest Pacific and Indo-West Pacific Oceans (30%)."

She is also an accomplished scientific illustrator. “I worked my way through college as a scientific illustrator,” Kimsey said. “In those days women weren't hired as lab or research assistants. I switched to entomology when I came to UC Davis from UC San Diego.”

“I guess I started doing detailed pen and ink drawings in junior high. Then in high school, I worked summers as a volunteer lab assistant and professional SCUBA diver at San Diego State.”

At each site, Lynn surveyed approximately 800 meters of shoreline at low tide, and typically spent between 60 and 120 minutes. She collected, by hand, samples of all common invertebrate species larger than 1 mm from the surface of mudflats, rocks, or pilings, and from under rocks, tires, and boards (with the underside of the object and substrate below examined for invertebrates). She observed but did not collect insects or arachnids. She preserved her collected specimens in 3 percent formalin (soft-bodied specimens) or 70 percent methanol. She deposited selected specimens in the California Academy of Sciences' Department of Invertebrate Zoology.

Recalling how her research came to be published, Kimsey said that during the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, she began looking through her half-century-old notes. She contacted Carlton, an emeritus marine sciences professor from Williams College (Williamstown, Mass.) and director emeritus (1989-2015) of the Williams College-Mystic Seaport Maritime Studies Program (Mystic, Conn. Carlton is known for his research on the environmental history of coastal marine ecosystems, including invasions of non-native species and modern-day extinctions in the world's oceans. In 2013, he received the California Academy of Science's highest honor, the Fellows Medal.

They agreed the research contains important baseline information about intertidal macro-invertebrate biodiversity.

Kimsey located the largest number of native species in the Golden Gate region. “The shoreline has rocky shores, as well as sand/gravel beaches and piers,” they wrote. “This region has the strongest daily currents, influenced by the proximity of the Pacific Ocean. The largest number of native species were found here. Indeed, at the two most exposed stations at the Golden Gate, only one introduced species, the wood-boring isopod Limnoria tripunctata Menzies, 1951, was found.”

“Unpublished historical biodiversity data are frequently lost over time,” the scientists wrote. “Such data from earlier periods can serve as critical baseline information by which to assess long-term biodiversity shifts and environmental changes.”

Digital editor Eric Simons of the Bay Nature publication chronicled the research in an Aug. 18th piece titled “Scientists Resurface a One-of-a-Kind, 50-Year-Old Record of San Francisco Bay Life.”

Kimsey and Carlton told him that they hope the project will inspire other scientists to proceed with similar research in the San Francisco Bay. But they wonder if this will ever happen.

“It's not hot and sexy,” Kimsey told Simons. “Hot and sexy is going to Costa Rica and playing in coral reefs. And that's really what attracts people. Getting down and dirty in the suburbs, it takes a different attitude about a whole different subject area.”