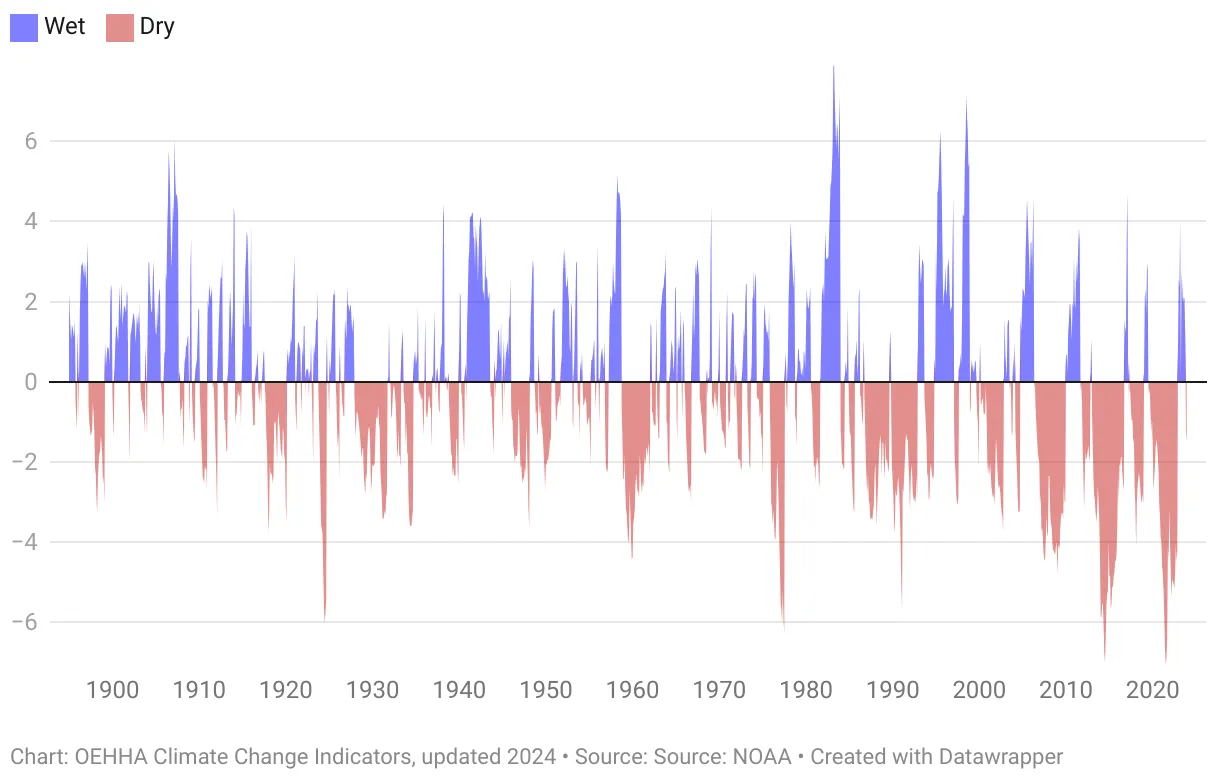

Droughts in California: A Frequent Challenge

Subject to severe short and long-term drought conditions, California has experienced two consecutive multiyear droughts in the past decade (Figure 1). The drought of 2012–2016, was considered one of the most severe on record, with record-low snowpack and precipitation. Although, conditions ameliorated with above average rainfall in 2017 and 2019, the effect of dry conditions and warmer-than-average temperatures lead to the 2020-2022 drought to being the driest three-year period in California history (Gamelin, B.L., Feinstein, J., Wang, J. et al., 2022). Multi-year droughts have always occurred in California and are expected to become more frequently and severe due to rising temperatures, increased number of hot extremes, prolonged heat waves and shifting precipitation patterns.

Figure 1. California Palmer Drought Severity Index (monthly, January 1895-December2023. Chart: OEHHA Climate Change Indicators, updated 2024. Source: NOAA

Under extreme drought conditions, reduced surface water deliveries often lead to increased reliance on groundwater pumping. While this can temporarily sustain water supply, prolonged dry periods ultimately result in declining groundwater levels, causing wells to run dry and severely affecting groundwater-dependent communities. The impacts of drought vary across the state. However, the adverse effects of drought are often more pronounced in disadvantaged communities, facing the greatest risks, often due to the lack of resources to adapt. Community water systems, small water systems, and households that rely on private domestic wells are particularly vulnerable to water shortages and water emergencies.

This underscores the urgent need for state intervention and targeted, community-driven strategies to strengthen long-term water security and resilience. Localized drought planning is essential to addressing these disparities and ensuring that all Californians have access to safe, reliable water in the face of an increasingly uncertain climate.

How California is Taking Action: Senate Bill 552

In 2021, during the midst of one of the most severe droughts of the past 20 years, Governor Newsom passed and signed Senate Bill (SB) 552, under which state and local governments to share responsibility in planning and responding to water shortage events, triggered by droughts. This bill, requires all counties to improve drought and water shortage preparedness for state small water systems and domestic wells within their jurisdiction by two main tasks, the first one is convening a standing drought task force to facilitate drought and water shortage preparedness for state small water systems (systems serving 5 to 14 connections), domestic wells, and other privately supplied homes with the County, and second, is to develop a plan demonstrating the potential drought and water shortage risk and propose interim and long-term solutions for state small water systems and domestic wells within the County.

County Drought and Water Shortage Task Force

To comply with SB552 counties should set up a standing Task Force with participation of local governments and stakeholders to facilitate drought related management actions and plan implementation. The Task Force serve as a coordination hub to support effective and efficient implementation of emergency responses, and it should include core members that are legally responsible for public water systems, state small water systems, and domestic wells. Some of these members could be well-permitting agencies (e.g., counties), county emergency management units (e.g., County OES), tribal representatives, Groundwater Sustainability Agencies (GSAs), representatives from large public water systems, community members, among others. Having a taskforce per county allows for localized strategies, rather than a one mold fits all, this approach allows counties to tailor drought strategies to their specific water challenges, ensuring more effective management and response.

Drought Resilience Plan (DRP): A Strategic Framework

Per SB 552, the County DRP may be a stand-alone that integrates comprehensive and accessible reference information and guidance to future drought response efforts, or integrate elements of the County DRP into existing plans, such as a local hazard mitigation plan (LHMP), emergency operations plan, climate action plan, or general plan. The minimum content required to be included in the DRP are: (1) Consolidations for existing water systems and domestic wells. (2) Domestic well drinking water mitigation programs. (3) Provision of emergency and interim drinking water solutions. (4) An analysis of the steps necessary to implement the plan. And (5) An analysis of local, state, and federal funding sources available to implement the plan.

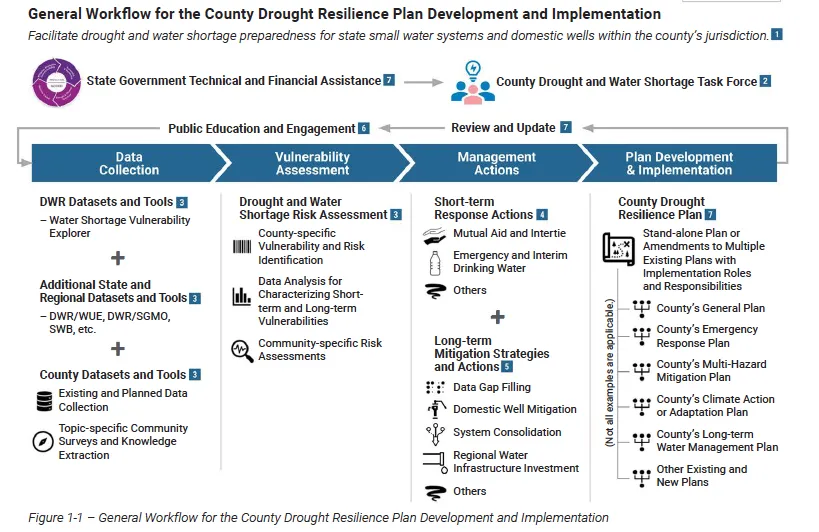

The DRP strategic framework (Figure 2), provides an overview of the general workflow for the County Plan Development and Implementation, and is structured in a four-step process:

Figure 2. General Workflow for the County Drought Resilience Plan Development and Implementation. (DWR. 2023)

- Data Collection: The data collection process draws upon using a wide range of state, regional, and county-level resources to inform drought resilience planning. Key tools and datasets include the Department of Water Resources' Water Shortage Vulnerability Explorer, Water Use Efficiency Data (WUEdata), California Statewide Groundwater Elevation Monitoring (CASGEM), Well Completion Report Map, Dry Well Reporting System. Additional resources include the State Water Resources Control Board's Water Use Objective (WSO) Exploration Tool and SAFER . These datasets are complemented by county-specific inventories, reports, and internal databases that track water systems, domestic wells, and related infrastructure. Furthermore, direct input from communities is obtained through surveys, interviews, and stakeholder engagement efforts to ensure that local knowledge and experiences are incorporated into data analysis and decision-making.

Vulnerability & Risk Assessment: The vulnerability and risk assessment aims at understanding how water shortages may affect residents, water systems, and local environments. Counties begin by identifying areas most susceptible to shortages, focusing on regions with dense concentrations of domestic wells, private surface water intakes, and state small water systems. Historical drought records are reviewed to identify patterns and geographic areas where impacts have been most severe, and where vulnerabilities are likely to persist or intensify.

The vulnerability assessment evaluates both physical and social dimensions. Physical vulnerability includes factors such as land use, climate, geology, and infrastructure conditions, while social vulnerability considers demographics, income levels, and reliance on limited water sources. These insights will assess which populations and systems are most at risk, the nature of their reliance on vulnerable water resources, and the reasons for that vulnerability.

The risk assessment builds upon the identified vulnerabilities by examining how these vulnerabilities intersect with specific drought and water shortage hazards and characterizes the likelihood and consequences of drought-related hazards using risk matrices. These matrices support a structured analysis of drought risks by weighing the probability of occurrence against the severity of their impacts and the results guide prioritization of mitigation actions. The findings from the vulnerability and risk assessment will form the foundation for identifying priority areas, developing response strategies, and implementing short and long-term drought mitigation measures that are responsive to the specific needs and risks of each county.

Response & Mitigation Strategies: Counties are expected to develop both short-term response actions and long-term mitigation strategies to reduce the risks associated with droughts and water shortages.

Short-term response actions are designed to address vulnerabilities quickly and reduce immediate impacts during the early stages and throughout ongoing drought or water shortage events. Several key actions that counties may consider include mutual aid agreements, interties or interconnections between water systems that permit the exchange or delivery of water and streamlined permitting and coordination processes. Additional measures include providing emergency and interim drinking water supplies through water filling stations, treatment of available water from alternative sources not typically used, packaged or bottled water (including storage and distribution), water hauling or bulk water delivery, and establishing partnerships with non-governmental organizations. Counties should also define triggers that activate response actions and establish clear implementation protocols.

In contrast, long-term mitigation strategies aim to reduce future vulnerability and dependence on emergency responses. The feasibility of implementing these strategies varies by county, depending on specific vulnerabilities, available financial, technical, and human resources, and the level of political and public support. Counties are encouraged to explore creative, sustainable solutions although, DWR provides guidance on several key long-term strategies, including drinking water well mitigation programs, system consolidation planning, and regional water infrastructure investment.

- Plan Implementation: The County DRP is to be implemented through a coordinated effort across departments and units within the county, in collaboration with other state and local agencies. This section should serve as a roadmap, outlining key considerations for effective implementation, including roles and responsibilities, timelines, and interagency coordination. As counties develop their County DRP, several items should be considered including Policy alignment for implementation, including adaptive management, transparency, and accountability with routine updates to reflect changed conditions and availability of new data. And lastly, Counties should also address funding availability to support implementation, identifying relevant programs and assistance opportunities.

Comparison of Drought Resilience Plans: The North Coast and the Central Valley

Mendocino is a coastal county in Northern California characterized by a cool, wet climate and a rugged topography with significant forest and watershed areas. It receives an average of 40 to 60 inches of precipitation annually, with the highest rainfall near the coast. Mendocino’s irrigated commodities are dominated by wine grapes, orchards, other specialty crops, and rainfed forages. Its population is under 90,000, distributed across dispersed communities. Notably the region's limited water storage infrastructure further exacerbates drought impacts, particularly for domestic well users. For instance, in the 2020–2022 drought, Mendocino was one of the first counties in the state to be declared in a drought emergency, and during this period the City of Fort Bragg, located in the coast, nearly exhausted its water supply, impacting also those of surrounding areas that typically rely on purchasing water from the Fort Bragg during shortages. In response, the County and the City of Ukiah took unprecedented emergency action, hauling water over 70 miles to Fort Bragg to provide a critical replacement supply.

Figure 3. Lake Mendocino storage levels. Source: MendoFever, 2021.

Tulare is located in the Central Valley of Southern California, an area that receives only about 10 to 12 inches of rainfall per year and relies heavily on groundwater. Tulare County’s agricultural strength is based on dairy production and a wide diversity of the crops including fruit and nuts, field crops, vegetable crops, and nursery products. The county's population exceeds 470,000 and includes several disadvantaged rural communities that have repeatedly faced complete water loss during recent droughts. Areas such as East Porterville and Teviston have endured prolonged periods without running water, with residents dependent on trucked bottled water year-round. Groundwater overdraft is a chronic issue in the Tulare Lake Hydrologic Region, where over 70% of monitored wells showed declines between 2018 and 2023, contributing to widespread land subsidence and long-term aquifer depletion.

These hydrological and socio-economic differences are clearly reflected in each county's DRP. Mendocino, with 7,972 domestic wells, has reported only 36 dry wells since 2014, just 0.5% of its total, yet risk analysis indicates that 84% of domestic wells and 93% of state small water systems remain at high risk. This risk is linked to the prevalence of shallow wells, many under 100 feet deep, lack of storage infrastructure, and poor water supply redundancy in rural areas. Tulare, with 6,338 domestic wells, has experienced over 1,856 dry well reports, aproximately 29% of its total, revealing higher groundwater vulnerability. Despite a higher number of small suppliers, Tulare reports only 57% at risk, perhaps reflecting a greater regional coordination.

The counties also differ in their response frameworks (Table 1). Mendocino's DRP distinguishes between its coastal and inland hydrologic regimes and uses localized data sources such as California Water Watch and reservoir levels to monitor conditions. Tulare applies broader hydrologic indicators, including DWR Bulletin 120 and changes in groundwater levels. Both plans include robust short-term actions—such as community engagement, mutual aid coordination, emergency water supply provisioning, and temporary ordinances—but Tulare also addresses renters’ rights, reflecting its higher population density and housing diversity. In terms of long-term adaptation, Mendocino emphasizes improved hydrogeologic understanding and the establishment of a drinking water well mitigation program, while both counties prioritize system consolidation, sustained monitoring, and coordination with state and federal programs. These differences underscore how regional climate, hydrogeology, and socioeconomic conditions fundamentally shape drought planning priorities and implementation pathways.

Table 1. Drought Resilience Plans Comparison | |||

North Coast Mendocino | Central Valley Tulare | ||

| Domestic wells and Small Water Suppliers | |||

| Number of domestic wells | 7972 | 6338 | |

| Number of reported dry domestic wells (since 2014) | 36 | 1856 | |

| Percentage of dry wells reported | 0.5% | 29% | |

| Domestic Wells at Risk | 84% | Not mentioned | |

| Number of small water suppliers (less than 14 connections) | 27 | 37 | |

| State Small water suppliers at risk (Less than 14 connections) | 93% | 57% | |

| Response Triggers | |||

| Geographic Focus | Coastal and Inland | No geographic focus | |

| Dry well reports | X | X | |

| Current Hydrology | California Water Watch for Precipitation (coastal) and Reservoir levels (inland) | DWR Bulletin 120 | |

| U.S. Drought Monitor | X | ||

| Groundwater Level Change | X | ||

| Short Term Response Actions | |||

| Monitoring Response Triggers | X | X | |

| CDTF (Convene CDTF meetings and increase frequency as necessary) | X | ||

| Drought Task Force, GSA, NGOs coordination | X | X | |

| Facilitation of mutual aid agreements | X | X | |

| Identification of funding | X | X | |

| Community engagement and outreach | X | X | |

| Voluntary water cutbacks | X | X | |

| Temporary Ordinances and Permit Streamlining | X | X | |

| County emergency proclamation | X | X | |

| Seek state and federal emergency declarations | X | X | |

| Emergency and interim water supplies (filling stations, water hauling, bottled water) | X | X | |

| Evaluate enforcement of renters’ rights | X | ||

| Long Term Response Actions | |||

| Improving Understanding of County’s Water Supply Resources and Hydrogeology | X | ||

| Drinking Water Well Mitigation Program | X | ||

| System Consolidation | X | X | |

| Tracking and Monitoring | X | ||

| Community Engagement and Outreach | X | X | |

| Implementation Considerations | |||

| Identified State, County, and local planning documents | X | X | |

| Identified leading agencies | X | X | |

| Identified State and Federal Assistance Programs | X | X | |

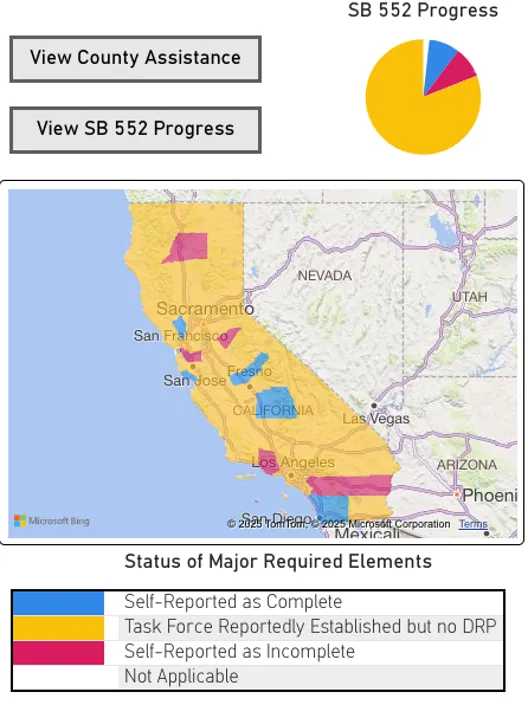

Status of Drought Resilience Planning in California

To support counties in complying with SB 552, the DWR County Drought Resilience Planning Assistance Program was established. This program provides financial and direct technical assistance and serves as a hub for essential resources for counties. This includes updates on county activities, the California County Café webinar series, financial and direct technical assistance, and links to tools like the Water Shortage Vulnerability Explorer and the County Drought Resilience Planning Guidebook.

So far in the first quarter of 2025, Madera, Napa, San Diego, Santa Cruz, and Tulare are reported as having an established Task Force and a Completed DRP. While Alameda, Calaveras, Riverside, Shasta, and Ventura are reported as not established Task Force, and the rest of counties have already established a Task Force and their DRP is in progress.

If you’re interested on the status of your County. The DWR County Drought Resilience Planning Assistance Program has an interactive dashboard (Figure 4.) that contains data gathered through direct communication with counties.

Figure 4. DWR Drought Resilience Dashboard

References

DWR (2023). County Drought Resilience Plan Guidebook: Task Force Formulation, Plan Development, and Implementation Considerations for Implementing Senate Bill 552 (Hertzberg). Guidebook.

Mendocino County Water Agency (2025). Mendocino Drought Resilience Plan. Report.

Tulare County (2023). SB 552 Drought and Water Shortage Risk Analysis and Response Plan. Report.

Medellín-Azuara, J., Escriva-Bou, A., Abatzoglou, J.A., Viers, J.H, Cole, S.A., RodríguezFlores, J.M., and Sumner, D.A. (2022). Economic Impacts of the 2021 Drought on California Agriculture. Preliminary Report. University of California, Merced. Available at http://drought.ucmerced.edu

Gamelin, B.L., Feinstein, J., Wang, J. et al. (2022) Projected U.S. drought extremes through the twenty-first century with vapor pressure deficit. Sci Rep 12, 8615. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-12516-7