Introduction

Youth don’t learn in a vacuum—they learn in different places and with different people. Learning can happen at school, while hanging out with friends at the park, or in a 4-H community club. All of these contexts provide youth with opportunities to interact with others and with their environments (Bronfenbrenner, 2007), which can provide rich learning experiences. Researchers call these learning spaces developmental contexts (Lerner, 1991; Hill, 1983).

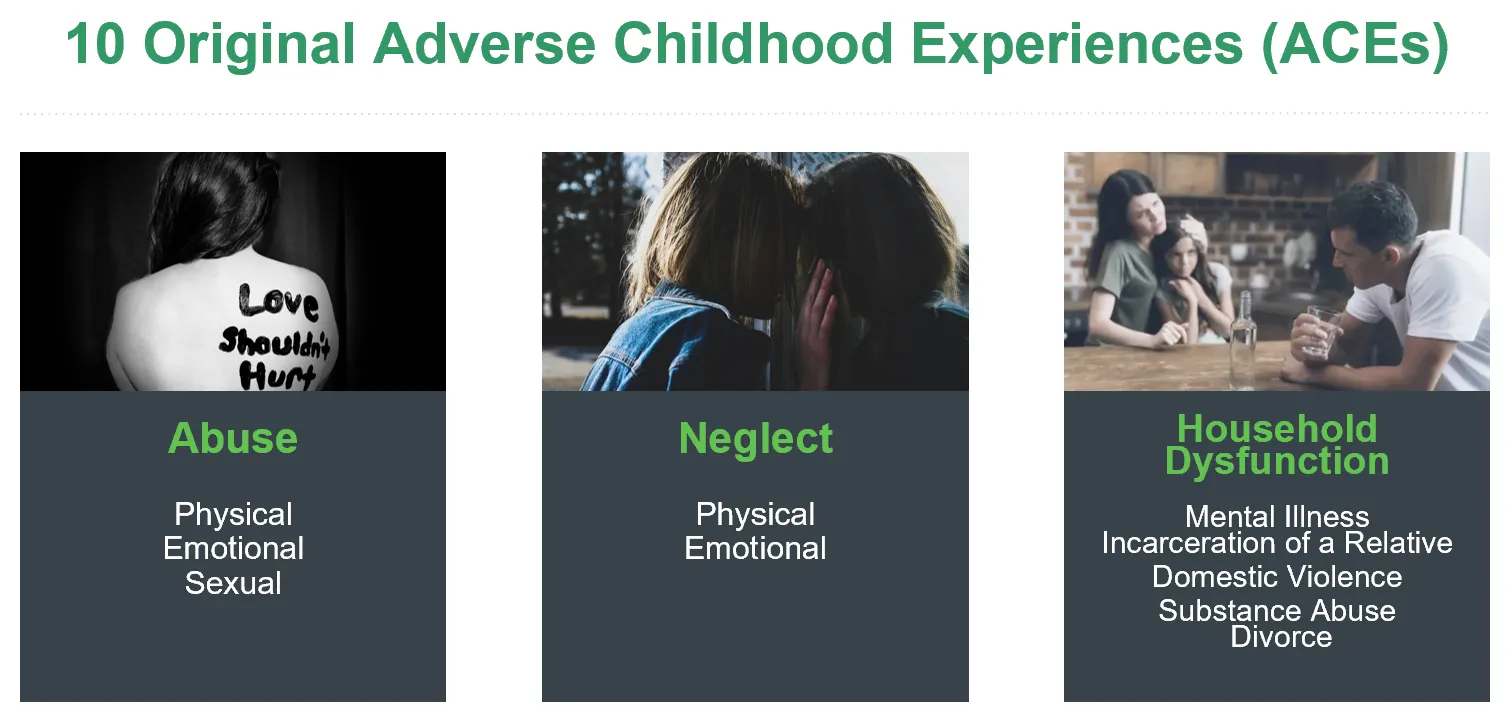

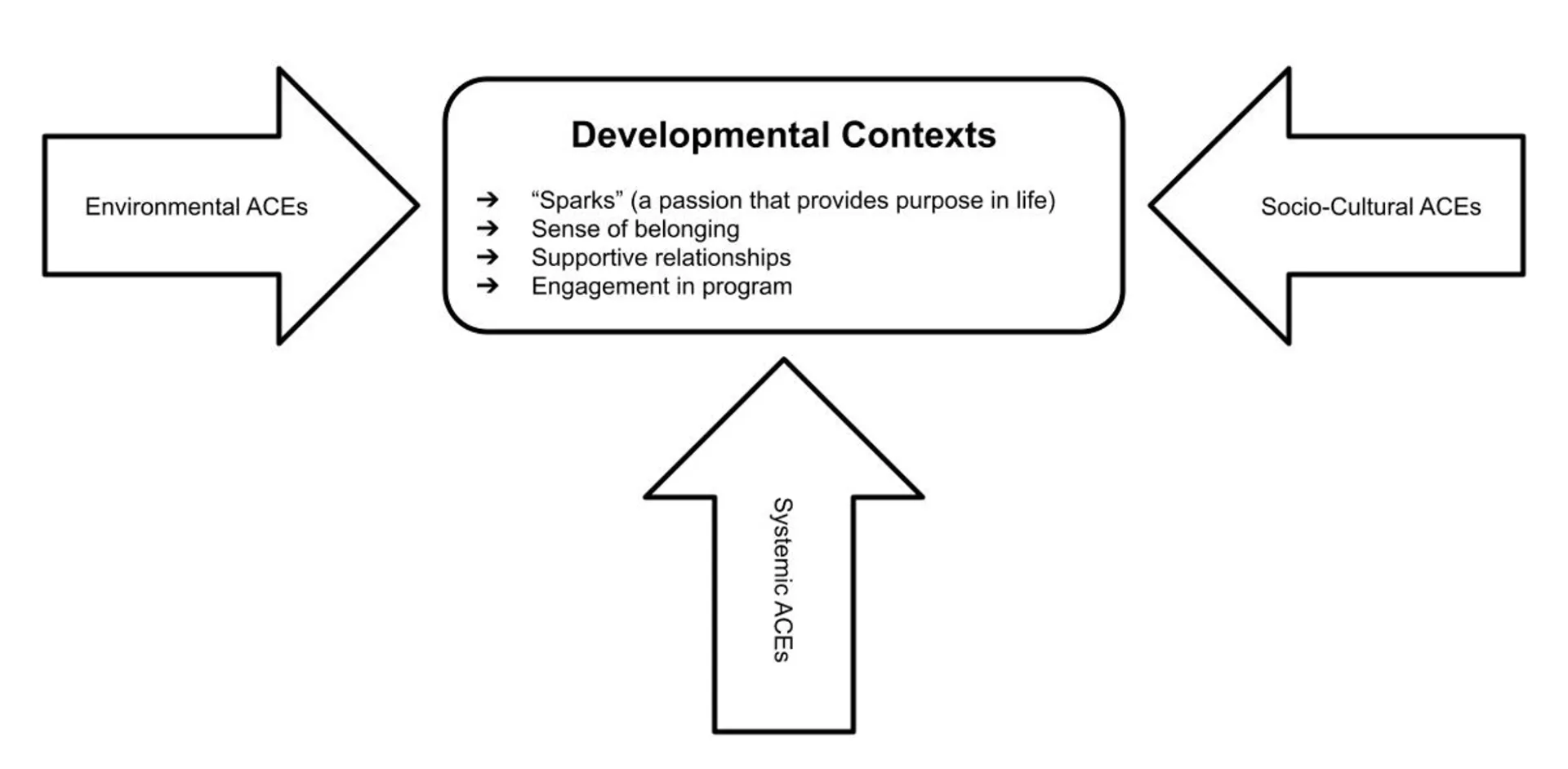

Just as learning doesn’t occur in a vacuum, developmental contexts also don’t occur in a vacuum. Learning contexts can be influenced both positively and negatively by outside factors. For example, Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), which can be environmental, systemic, and socio-cultural factors (e.g. exposure to pollution, racism/discrimination, and bullying) can prove challenging to our wellbeing. ACEs can inhibit a youth’s opportunity to experience healthy developmental contexts, such as their ability to find their passions, known as “sparks,” sense of belonging, supportive relationships, and program engagement (Arnold, 2020; Fields, 2020).

For those of us who work with youth, having an understanding of ACEs can inform our understanding of factors that can inhibit or reduce a young person’s access to healthy developmental contexts. The information below discusses the relationship between ACEs and youth developmental contexts.

Figure 2. Expanded conceptualization of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs)

4-H Thriving Model of Positive Youth Development

While the 4-H Thriving Model of Positive Youth Development outlines the importance of developmental contexts, the model is limited in illustrating the environmental, systemic, and socio-cultural factors that can negatively impact youth wellbeing. As such, the expanded list of ACEs can provide important context to the 4-H Thriving Model of youth development by explaining exogenous or outside factors that can influence youth development. Below are some ways that ACEs can inform our understanding of 4-H sparks, belonging, relationships, and program engagement (Arnold, 2020; Fields, 2020).

4-H Sparks

4-H “sparks” are passions that youth self-identify whereby they can positively impact their community. Some youth are passionate about community service, such as volunteering. The expanded ACEs framework helps us understand that youth who are exposed to systemic factors, such as racism and discrimination, may not have access to certain volunteer opportunities. As such, youth practitioners can expose youth who experience racism and discrimination to new volunteer opportunities that they may not have previously had access to. Writing a strong letter of support for a marginalized youth can provide one means of helping them “get their foot in the door.”

Belonging

Belonging is the idea that all youth and adults feel included in the 4-H program. The expanded ACEs framework helps us understand that environmental factors, such as lack of reliable public transportation, can negatively impact youth. For example, a youth living in an economically disadvantaged rural community with limited busing may find it difficult to attend youth programs, such as a 4-H club meeting. Transportation access can prove especially challenging for families who are economically insecure and don’t have a car. Youth programs can increase a youth’s sense of belonging by conducting a brief transportation needs assessment with each parent or caretaker to better understand whether prior travel arrangements are needed.

Relationships

Healthy relationships are important for youth because it allows others to express care for their wellbeing. The expanded ACEs framework helps us understand that socio-cultural factors, such as school bullying, can have deleterious effects on the mental, physical, and emotional well-being of young people. Youth who experience bullying may close themselves off to others due to mistrust and trauma. As such, youth practitioners can show empathy and patience with youth who are hesitant to allow others to express care for their wellbeing.

Engagement

Program engagement describes youth who can fully participate in and enjoy the 4-H experience, such as learning about animals, making friends, and practicing new skills. The expanded ACEs framework helps us understand that youth who experience systemic factors, such as poverty, may not have the economic means to engage in certain 4-H learning experiences, such as raising a silkie chicken. Families who live in poverty may change home addresses every few months as they struggle to pay rent. As such, they may not have the resources needed to raise a chicken. To address this, 4-H project leaders can consider supporting the individual resource needs of youth struggling with poverty.

By incorporating an understanding of the expanded ACEs, youth practitioners can be mindful of the different challenges our youth face daily. Through careful reflection of these challenges, we can help increase youth's access to developmental contexts, such as sparks, belonging, relationships, and program engagement.

Re-conceptualizing developmental contexts to include ACEs

Figure 3. Conceptualization of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and their relation to developmental contexts (Rodriguez, 2025)

Application of ACEs to our ordinary lives

- How can environments influence a youth’s ability to engage in school or a youth program, such as 4-H?

- Has one of your youth (and/or yourself) experienced bullying? How can we support those who are experiencing bullying so they can experience positive relationships?

- Do you feel that economic insecurity is related to a person’s sense of belonging? Why or why not?

- Have you ever struggled in school? How may youth who struggle in school find it difficult to find their passion in life (e.g. spark)?

References

Arnold, M. E., & Gagnon, R. J. (2020). Positive youth development theory in practice: An update on the 4-H Thriving Model. Journal of youth development (Online), 15(6), 1-23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5195/jyd.2020.954

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2007). The Bioecological Model of Human Development. Handbook of Child Psychology, 793-828. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0114

Fields, N. I. (2020). Exploring the 4-H Thriving Model: A Commentary Through an Equity Lens. Journal of youth development (Online), 15(6), 171-194. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5195/jyd.2020.1058

Hill, J. (1983). Early adolescence: A framework. Journal of Early Adolescence, 3, 1–21.

Lerner, R. M. (1991). Changing organism-context relations as the basic process of development: A developmental-contextual perspective. Developmental Psychology, 27, 27–32.

Rodriguez, M. R. (2025). Conceptualization of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and their relation to developmental contexts.