In the past, selenium deficiencies were common in places like Oregon, but due to extensive selenium supplementation throughout the state, WMD and other selenium deficiency disorders are now infrequent6. In California, on the other hand, selenium deficiencies continue to be an important health risk to livestock in more than 60% of the state's herds7. This article will focus on WMD caused by selenium deficiency in California beef cattle.

WMD can affect cardiac, respiratory, and skeletal muscle tissue4. Cattle whose cardiac muscles are affected can have respiratory problems, cardiac arrhythmias, or can die. Respiratory problems can also manifest in animals whose respiratory muscles are affected. Those with WMD affecting their skeletal muscles may experience stiffness, and weak damaged muscles, particularly in their hind legs, making it difficult to stand or nurse4,8,9. As the muscle degeneration occurs, calcium salts are incorporated into striated muscle fibers causing whitish lines, which is where the name white muscle disease comes from3,9. Treatment of cattle with cardiac WMD is ineffective and animals usually die in less than 24 hours4. These animals are typically between a few days to a few weeks old8. Treatment for animals with skeletal WMD, on the other hand, can be effective and improve their condition in 3-5 days4.

Calves born from cows that have adequate selenium will themselves have adequate stores of selenium for 30-60 days after they are born8. However, calves will not able to effectively obtain selenium from their mother's milk. One study showed that nursing calves, without access to supplemental selenium, became either low or deficient in selenium, even when their mothers were provided with optimal amounts of selenium10. The one exception was cows supplemented with an organic form of selenium (selenium-yeast) through a free-choice mineral mix. Organic mineral forms are known to have high rates of absorption and are effective at circulating minerals throughout the blood stream8.

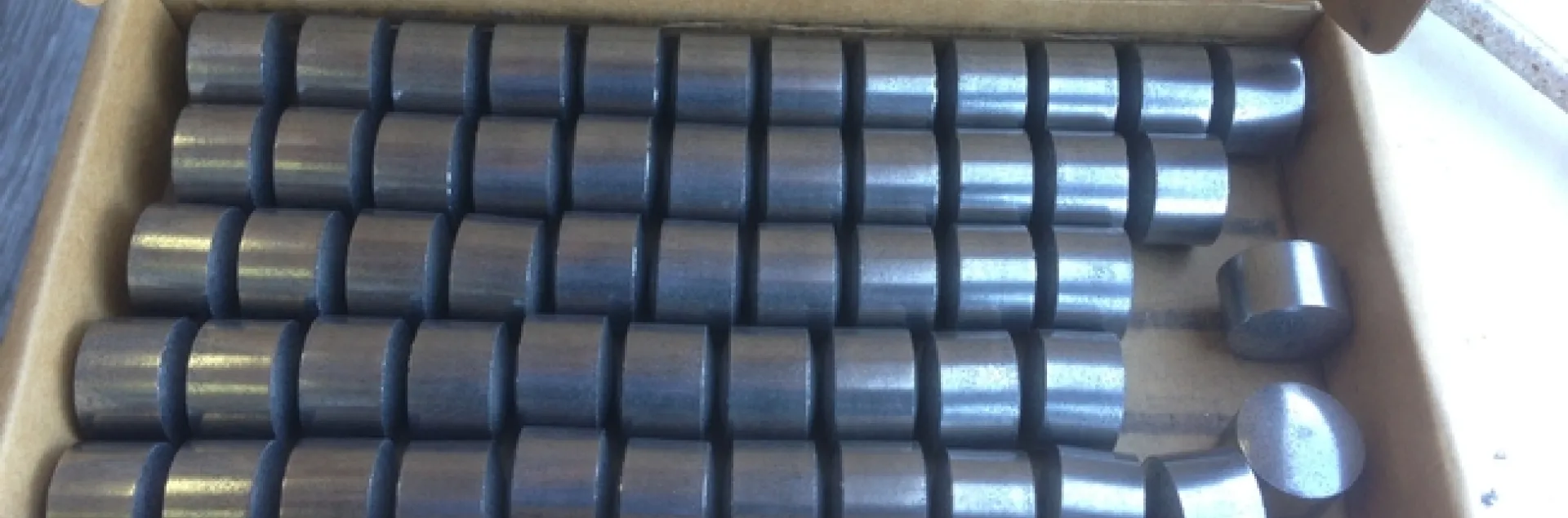

In order to prevent WMD and other selenium deficiency disorders, cattle can be given selenium supplements that can be injected, or provided through mineral mixes or a bolus5 (Figures 2 and 3). The bolus is only legal in California11. Supplementing pregnant or lactating cows and newborn calves is particularly important in order to avoid WMD3. Selenium also has the potential to be toxic and is therefore regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. The maximum allowed by law in a salt mix is 3 mg of selenium (about 1 ounce of salt mix) per animal per day2. This is the recommended amount. Selenium supplementation can come in 2 forms: inorganic or organic11. Inorganic selenium can be provided as sodium selenite or sodium selenate salts. Sodium selenite is the more commonly used because it is readily available. Selenomethionine is the organic form of selenium and is able to integrate into muscle tissue. Because of this, it remains in the body of ruminants substantially longer than inorganic forms of selenium. Thankfully, WMD is a disease that can be treated. Many California livestock producers will improve cattle health and profits if they are able to implement an effective selenium supplementation program.

CITATIONS

1CAHFS Laboratory System Annual Report 2000. 2001. School of Veterinary Medicine, UC Davis. pp. 24 25.

2Maas, J. 1998. Trace Minerals for Cattle: An Update. UC Davis Vet Views, California Cattlemen, November 1998. http://ucanr.edu/sites/UCCE_LR/files/151748.pdf, last accessed 7/31/2016.

3Pond, W.G., D.C. Church, K.R. Pond, and P.A. Schoknecht. 2005. Basic Animal Nutrition and Feeding, 5th edition, John Wiley & Sons Inc., New York.

4Valberg, S.J. 2014. Nutritional Myopathies in Ruminants and Pigs. The Merck Veterinary Manual. Last full review/revision April 2014 by Stephanie J. Valberg, DVM, PhD, DACVIM, ACVSMR. http://bit.ly/2aCX1vl, last accessed 7/31/2016.

5Forero, L., Drake, D., Nader, G. 2008. Summary of Selenium, Copper and Zinc Status for Beef Cattle in Northern California. Northern California Ranch Update. Volume 2. Issue 1. http://bit.ly/2aa2mu0, last accessed 7/31/2016.

6Oldfield, J.E., 1989. Selenium in animal nutrition: the Oregon and San Joaquin Valley (California) experiences—examples of correctable deficiencies in livestock. Biological trace element research, 20(1-2), pp.23-29. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2484399, last accessed 7/31/2016.

7Dunbar, J. R, B. B. Norman, and M. N. Oliver. 1988. Preliminary report on the survey of selenium whole blood values of beef herds in twelve central and coastal California counties. Pages 81-83. Selenium contents in animal and human food crops grown in California. Cooperative Extension, University of California Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Publication 3330. Oakland, California.

8Hall, J.B. 2006. Selenium Supplementation Strategies for Cow/Calf Herds. The Cow-Calf Manager Newsletter. April 2006. Virginia Cooperative Extension. Virginia Tech, Virginia State University. http://www.sites.ext.vt.edu/newsletter-archive/livestock/aps-06_04/aps-313.html, last accessed 8/3/2016.

9Hansen, D., R. Hathaway, and J.E. Oldfield. 1993. White muscle and other selenium-responsive diseases of livestock. PNW 157. Revised May 1993. http://www.multiminusa.com/sites/www.multiminusa.com/files/pdfs/se_responsive_diseases.pdf, last accessed 8/3/2016.

10Davis P.A., L.R. McDowell, R. Van Alstyne, T.T. Marshall, C.D. Buergelt, R.N. Weldon, and N.S. Wilkinson. 2005. Case Study: Tissue and Blood Selenium Concentrations and Performance of Beef Calves from Dams Receiving Different Forms of Selenium Supplementation. Prof. Anim. Sci. 21:486-494.

11Brummer, F.A., G.J. Pirelli, and J. A. Hall. 2014. Selenium Supplementation Strategies for Livestock in Oregon. Oregon State University Extension Service. http://bit.ly/2aUBU4P, last accessed 7/31/2016.

12Davy, J. 2015. Livestock, Range, and Natural Resources Advisor, University of California Cooperative Extension, personal communication.