Wilson, recognized as one of the world's most influential scientists, was known as “The Ant Man,” "The Father of Sociobiology," "The Father of Diversity" and “The Modern-Day Darwin," for his pioneering and trailblazing work that drew global admiration and won scores of scientific awards.

But among his peers, colleagues and mentees, he was known as "Ed."

Wilson's work, On Human Nature, won the Pulitzer Prize in 1979. He won a second Pulitzer in 1991 with The Ants, co-authored with colleague Bert Hölldobler. In 1990, the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences awarded Wilson the Crafoord Prize in biosciences, the highest scientific award in the field. In 1996, Time magazine named him one of America's 25 most influential people. In 1977 President Jimmy Carter awarded him the National Medal of Science for his contributions toward the advancement of knowledge in biology.

Wilson, according to reports, always considered himself an Alabaman who went to Harvard, rather than a Harvard professor born in Alabama. Born June 10, 1929 in Birmingham, Ed graduated from the University of Alabama in 1949 with two degrees in biology, and received his doctorate in biology from Harvard in 1955. He joined the Harvard faculty in 1956. Although officially retiring in 1996, he remained active as an emeritus professor and honorary curator until his death.

Some tributes from UC Davis faculty and students:

“E. O. Wilson was a towering figure in the study of social insects, in evolutionary biology, and in conservation biology,” said fellow ant specialist and professor Phil Ward of the UC Davis Department of Entomology and Nematology who organized the 2007 E.O. Wilson Festschrift (a collection of writings published in honor of a scholar). “He made important contributions in all of these areas, but his specialty was the study of ants, those ‘little creatures that run the world.' Wilson's book, The Insect Societies (1971), introduced its readers to the fascinating world of ants and other social insects, using language that was both engaging and accessible, yet highly informative.”

“This was followed two decades later by the equally magisterial The Ants, co-authored with Bert Hölldobler,” Ward noted. “These landmark contributions inspired many budding biologists, myself included, to devote ourselves to the study of ants and other social organisms. Equally important, Wilson argued passionately and compellingly for the conservation of biological diversity in a dwindling natural world. He once said that 'destroying rainforest for economic gain is like burning a Renaissance painting to cook a meal.' Let us honor his legacy by heeding this message!”

UC Davis doctoral alumnus Brendon Boudinot of the Phil Ward lab and now a postdoctoral researcher in Germany at the Institute of Zoology and Evolutionary Research, Friedrich Schiller University Jena, says the ant world is reeling with Wilson's passing. “A big chunk of my dissertation was dedicated to testing his hypotheses for the origin and early evolution of ants!”

Boudinot met Wilson when he was visiting the Ant Room at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology in 2013. “The work I was doing was the foundation for my studies on ant males, and I was near the end of the trip, at one of the many microscopes by the window facing the yard,” he said. “Ed surprised me by coming right up to my shoulder at the scope; he asked me what I was working on. I am a bit abashed to say that I couldn't say anything because my mind went blank! Stef Cover, the pins-and-points curator told Ed what I was doing, and for the life of me I will always remember what Wilson said. He was happy that I chose to work on male ants, when this sex has been actively ignored by researchers over the past centuries, and that he himself was more apt to squash one at a light trap than to collect one. I hope that my keys and diagnoses have helped people appreciate male ants.”

“I am so thankful that I met him,” Boudinot said, “and that I was able to work with so many people in his sphere. The ant world is reeling, as he was a gentle giant of myrmecology, and of course biology writ large.”

Doctoral candidate Jill Oberski of the Phil Ward lab met “The Ant Man” in 2019. “I got to meet E. O. Wilson when I traveled to the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology in 2019. In addition to myself, there were several other researchers visiting the “Ant Room,” which houses a huge number of type specimens.”

“He asked me about my research on Dorymyrmex taxonomy and biogeography, although as a second-year PhD student I didn't have much to report yet. He was genuinely interested in my work and excited that I was working to resolve Dorymyrmex--which has always been a taxonomic headache. He also told me he recalled watching ants forming cone-shaped nests as a child in Alabama, which could only have been Dorymyrmex. He was exceedingly kind and encouraging.

“Finally, the Ant Room staff and visitors ate lunch together in Ed's office—lobster sandwiches, diet Dr. Pepper, and coffee, as is customary.”

Lynn Kimsey, director of the Bohart Museum of Entomology and a UC Davis distinguished professor of entomology, remembers working near his office when she served as a visiting professor/lecturer (1987 to 1989) at Harvard's Museum of Comparative Zoology, before joining the UC Davis faculty in 1989.

“His office was just down the hall from mine when I taught at Harvard. Here he was, one of the most famous biologists of his generation and I would see him sit down on the sidewalk to show a little kid the ants there. Also, saw him in the sitting on a bench Burlington Mall while his wife shopped, writing on a yellow pad of paper. Totally focused on what he was writing with shopping pandemonium all around. He was brilliant, humble and engaging.”

UC Davis doctoral alumnus Fran Keller, a professor at Folsom Lake College, and a research scientist at the Bohart Museum of Entomology, helped honor his work at a special symposium hosted at the 2005 Entomological Society of America meeting in Fort Lauderdale, Fla.

"Our department of entomology helped fund my trip to Harvard,” she recalled, “and he agreed to meet me over the course of two days in May 2005. The ESA symposium took place in mid-December. I recorded our interview on a cassette tape,” she said, adding she hopes to publish it in a journal.

Wilson responded: “Everyone has an animal that reaches them or that they connect with at some level, even though you were born an entomologist, perhaps yours is the rhino.”

“After my interview with Ed, I bought the book in the MCZ, The Rarest of the Rare: Stories Behind the Treasues at the Harvard Museum of Natural History. In that book, it highlights the extinct and rare species held in the MCZ collections. One of those specimens is the last Xerces butterfly, which was caught by Harry Lange (UC Davis emeritus professor of entomology). Harry's quote in that book, ‘I didn't know it was the last one, I thought there would be more' and then my time eating lunch and then wandering the MCZ collection and chatting with Ed inspired me to create the Xerces t-shirt for the Bohart Museum of Entomology.”

One of Keller's mentors, Tom Schoener, studied with Wilson. “I worked on plant ecology and island biogeography for my undergrad research (Sacramento City College)," she said, "and continued that for awhile in grad school (UC Davis). Ed Wilson was one of the founders of island biogeography.”

As a undergraduate at Sacramento City College, Keller was part of a field trip to hear Wilson speak at his 2002 book tour on The Future of Life.

UC Davis doctoral alumnus Alex Wild, an evolutionary biologist, science photographer and curator of entomology at the University of Texas, Austin, wrote this on his Twitter account, @Myrmecos, which has more than 30,000 followers: “Ed Wilson was one of my science heroes. Over the years I came to admire two things in particular. One was his ability to craft technical books so compelling as to launch scores of scientific careers in their wake.”

“The other thing is how Ed Wilson handled professional disagreement," Wild tweeted. "And he had a lot of those, because Wilson was frequently wrong. About a great range of topics. For a guy known for ant research, his interpretation of ant origins was just… silly.”

"But he continued to support, both financially and professionally, the young upstarts who, over and over, proved him wrong. That's a rare trait for a field as ego-driven as evolutionary biology.”

When a follower asked: “Can you explain to a non-biologist bug enthusiast why his interpretation of ant origins was silly?”, Wild replied: “His arrangement of the ant subfamilies, based on subjective hunches of evolutionary relationships rather than data, bore no resemblance at all to the well-supported relationships from subsequent data-based studies, like https://www.pnas.org/content/103/48/18172. (This 2006 research article, "Evaluating Alternative Hypotheses for the Early Evolution and Diversification of Ants," is co-authored by Seán G. Brady, Ted R. Schultz, Brian L. Fisher, and Philip S. Ward and edited by Bert Hölldobler, University of Würzburg, Würzburg, Germany)

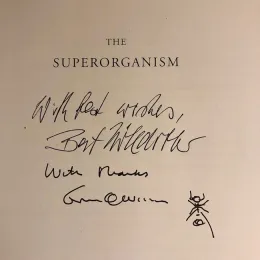

“There are no words that adequately describe E.O. Wilson's courage in challenging dogma, his energy in documenting and sharing the wonders of our planet, or his extraordinary creativity," said Diane Ullman, UC Davis professor of entomology and former chair of the Department of Entomology. "So much of his writing touched me deeply, from his writing about the continuum between art and science (Consilience), to his collaboration with Bert Hölldobler, addressing the incredible biology and behavior of social insects (Superorganism). He wrote a wonderful, 'coming of age' novel, seemingly much inspired by his own youth (Anthill)."

"The first time I was able to hear him speak in person was in 1996 at the International Congress of Entomology in Florence, Italy, where he was the plenary speaker opening the meeting. He spoke passionately about loss of biodiversity, and was sounding the alarm on impact of humans and climate change on the planet. He continued to lead this charge up to the very end, never giving up on proposing potential solutions on a global scale. He was witty and with use of metaphor made us see so very many things."

Caleb Johnson, who teaches writing at Appalachian State University, Boone, N.C., described E.O. Wilson as “the world's forestmost authority on biodiversity” in an April 21, 2020 article in The Bitter Southerner. He referred to him as “A world-renowned scientific thinker whose vision for stopping this unprecedented environmental hemorrhaging is based on more than seven decades of careful witness, writing, and work in ecology and conservation."

Johnson wrote that Wilson lost his right eye in a fishing accident in the summer of 1936 near Paradise Beach, Fla., but he never let that stop his goals.

"In the 1940s, E.O. Wilson was an Alabama teenager who wandered the bottomland around Mobile and studied its creatures. He never stopped and became the world's foremost authority on biodiversity. He's 90 now, but still working, because he knows there's a way to undo the damage we've done to Mother Earth."