“These weather-related catastrophes can cause local extinctions and disrupt ecological interactions,” wrote Carroll and three Texas collaborators in a newly published article in the journal, Nature Ecology and Evolution, “Spatial Sorting Promotes Rapid (mal) Adaptation in the Red-Shouldered Soapberry Bug after Hurricane-Driven Local Extinctions.”

“Such disruptions,” they related, “are expected to become more impactful and frequent in the near future and, consequently, so will the associated regularity of localized extinction and post-disturbance recovery.”

The research team, including Carroll and Mattheau Comerford, Scott Egan and Tatum La of the Department of BioSciences, Rice University, Houston, studied the changes the soapberry bugs went through after “catastrophic flooding in an extreme hurricane” in southeastern Texas.

They found that “long-winged dispersal forms of the soapberry bug, Jadera haematoloma, accumulated in recolonized habitats and due to genetic correlation, mouthparts also became longer and this shift persisted across generations.”

“Those longer mouthparts were probably adaptive on one host plant species but maladaptive on two others based on matching the optimum depth of seeds within their host fruits due to genetic correlation,” they wrote.

Hurricane Harvey, a Category 4 hurricane that made landfall in Texas and Louisiana in August 2017, is known as one of the worst tropical cyclones to hit the United States, resulting in more than 100 deaths and displacing more than 30,000 people. “In a four-day period, many areas received more than 40 inches (1,000 mm) of rain as the system slowly meandered over eastern Texas and adjacent waters, causing unprecedented flooding,” according to Wikipedia.

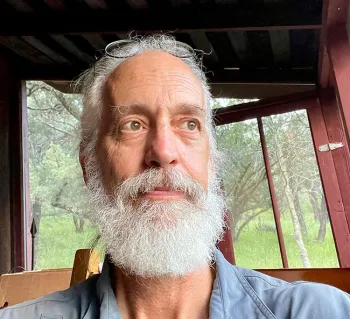

Carroll, who holds a doctorate in biology from the University of Utah, explores contemporary evolution “to better understand adaptive processes and how those processes can be harnessed to develop solutions to evolutionary challenges in food production, medical care and environmental conservation.” He is a research associate in the Department of Entomology and Nematology and the president of the Carroll-Loye Biological Research.“

"Recent work on the biology of invasive species has highlighted ‘spatial sorting' as an underappreciated evolutionary mechanism that relies on dispersal and, thus, promotes rapid evolution across space,” the team wrote.

The authors defined spatial sorting as “a process of dispersing organisms that generates non-random shifts in local phenotype frequencies, such that good dispersers are the first to arrive at the leading edge of invasions or in recolonized habitats. This leads to assortative mating, as only other strong dispersers are present during the time of colonization. For instance, in the current study, mate options at recolonized flooded sites were initially limited to macropterous individuals as wing form during colonization was 100% biased by the ability to fly. Spatial sorting could then be self-reinforcing, as offspring of colonizing individuals are expected to show similar or stronger dispersal phenotypes, along with a higher frequency of genetically correlated traits not associated with dispersal.”

“Soapberry bugs are well-known examples of rapid adaptive evolution in response to Anthropocene environments, where populations on native host species have shifted and adapted to feed on introduced, non-native plants in the same family over the past 60 years,” the authors wrote.

Soapberry Beaks. Soapberry bugs pierce seed pods with needle-like mouthparts, commonly referred to as “beaks.” “The range of mouthpart lengths in nature strongly reflects fruit size of the host plant on which each population feeds and these host-associated differences in beak length evolved through divergent natural selection between hosts,” the authors wrote. “When beak length matches the distance between outer fruit wall and the interior seeds, it increases seed access and decreases handling time, leading to higher fecundity in females. Beak length is a polygenic trait influenced by epistatic and dominance interactions and is highly heritable.”

The study involved three soapberry bug host plant species in the southeastern Texas study area: (1) native balloon vine (Cardiospermum halicacabum), with large inflated seed pods hosting soapberry bugs with the longest beak lengths; (2) native western soapberry tree (Sapindus saponaria var. drummondii, with intermediate-sized seed pods hosting soapberry bugs with intermediate-sized beak lengths; and (3) non-native goldenrain tree (Koelreuteria elegans) with comparatively flat capsules that permit ready access to the seeds.

The authors wrote that Hurricane Harvey “was locally catastrophic for the flooded soapberry bug study populations, with populations at 11 of the 15 monitored sites going locally extinct and remaining so for at least 4.5 months and seven additional populations never returning over the 3 years post-hurricane.” All of the drowned bugs were balloon vine associates; the pods are water dispersed; and many of the sites were deeply inundated. Yet those vines are the most regular seed providers in safe times, and favor the quick developing flightless bugs in consequence. Those individuals had little chance of escape.

Adjoining Viewpoint. In an adjoining viewpoint, titled “Spatial Sorting Creates Winners and Losers,” evolutionary ecologists Swanne Gordon and Caleb Axelrod of Cornell University's Department of Ecology and Evolution, said the research provides “evidence of the role of spatial sorting in recolonization by soapberry bugs after a catastrophic event.”

“We are currently experiencing a concerning increase in catastrophic environmental disturbances on Earth, which presents a pressing challenge for both ecological systems and human societies,” Gordon-Axelrod wrote. “These disturbances--encompassing events such as hurricanes, wildfires and droughts--can have marked short-term and long-term impacts on ecosystems.”

Comerford, Carroll and Egan conceived the focus of the paper; Comerford and La performed the data collection; and Comerford and Egan shared writing responsibilities with feedback from Carroll and La.

The project drew financial support from grants from the American Museum of Natural History, American Philosophical Society, Society for the Study of Evolution for dissertation support to Comerford, and the National Science Foundation to Egan and Carroll.

All data collected for this project are freely available in the digital repository Dryad: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.tht76hf4t.