Summer is pinkeye season

(this article is adapted from an article by the UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine and is based on the work of John Angelos, DVM, PhD; Dr. Angelos provided additional editing)

Pinkeye—or infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis—is the most common eye disease of cattle in California and throughout the U.S. Pinkeye causes pain and suffering in affected animals that negatively impacts overall animal welfare as well as economic losses to cattle producers. One 2005 study showed, for example, that calves that had previously had pinkeye were on average 20 pounds lighter than unaffected animals at weaning. And another, earlier study showed that bull calves one- year post-weaning were 51 pounds lighter if they had had pinkeye in one eye and 103 pounds lighter if they had had it in two eyes. These studies emphasize that prevention is of the utmost importance.

Pinkeye is caused by infection of the cornea with Moraxella bovis (M. bovis) bacteria and results in painful corneal ulcers and inflammation of the eye and skin surfaces lining the eye (conjunctiva). If not properly treated, corneal infections can result in corneal scars or even eyeball ruptures leading to permanent blindness. Another bacterium that has been associated with pinkeye, but which has not been experimentally shown to cause corneal ulcerations typical of pinkeye is Moraxella bovoculi (M. bovoculi). Currently there are vaccines on the market against both M. bovis and M. bovoculi (see below).

Pinkeye is most common in the summer months with increased exposure to sunlight and dry, dusty conditions. Some outbreaks also occur during winter months. Plant awns such as foxtails can also predispose animals to disease by getting caught in the eye and damaging the cornea. Flies also increase the chances of exposure and spread of M. bovis (and probably M. bovoculi) bacteria by feeding around the face and eyes of affected cattle and then transferring infected eye fluids to other animals. Humans might also help spread the disease particularly when they are not wearing disposable gloves or applying disinfectants to halters or other objects involved in handling affected animals.

Common signs of pinkeye:

-

Excessive tearing

-

Frequent blinking or squinting

-

Decreased appetite due to eye pain

-

Corneal ulceration and cloudiness

-

Potential blindness or eye rupture

-

Can affect one or both eyes

- Younger cattle typically more susceptible

Prevention:

Fly control: Controlling flies should help to reduce the risks of disease spread between animals in a herd. Traditional methods have included the use of insecticide-containing ear tags, dust bags, and systemically- or topically-applied parasiticides. A 1990s study looked at four different fly control strategies: 1) Ivermectin pour-on (0.5% pour-on @ 500ug/kg); 2) insecticide ear tags with permethrin (10%); 3) insecticide ear tags with diazinon (20%); and 4) Ivermectin plus ear tag in mid- summer. The best face fly control was the permethrin ear tags alone or in combination with Ivermectin (but not Ivermectin alone). Consider applying insecticide ear tags in the late spring/summer at preg-checking time. It is also a good practice to remove ear tags at the end of the fly season to help reduce chances for insecticide resistant fly populations to develop.

Weed control: Since foxtails and other plant awns can lead to corneal ulceration and eventual pinkeye, one recommendation is to clip pastures that have already seeded out before turning cattle onto that pasture.

Practice good sanitation/hygiene: To avoid inadvertently spreading infective bacteria between animals, use disposable gloves when handling pinkeye-affected cattle. These gloves should be changed or at least disinfected between animals. In addition, consider changing clothes or wearing a plastic apron when handling affected animals. It is a good practice to also disinfect plastic aprons and halters between cattle. One commonly used disinfectant is 10% household bleach made by mixing one part of regular strength household bleach to nine parts water (or ~1-1.5 cups regular strength bleach per gallon of clean water). If using concentrated bleach you will only need ~1/2 cup per gallon of clean water. This mixture should be made fresh daily to maintain effectiveness. Also, bleach becomes less effective when it becomes heavily soiled with dirt or manure and other organic material. For that reason it may need to be refreshed more frequently, depending on use and working conditions.

Trace minerals: Some trace mineral deficiencies in cattle have been linked to reduced immune responsiveness and might also lead to elevated rates of pinkeye. When it comes to pinkeye prevention, maintaining adequate levels of copper and selenium is particularly important in this part of the country. Other trace minerals/vitamins which may be important for maintaining optimum immune responsiveness and therefore might impact pinkeye prevalence include chromium, Vitamin A, Beta-carotene, cobalt, and zinc. This is yet another reason to make sure you have a robust trace mineral supplementation program on your ranch!

Vaccinate: Vaccination is another important component of pinkeye prevention, however, even with vaccination, producers may still experience pinkeye problems with today's vaccines. When vaccinating animals, it is important to vaccinate well in advance (ideally start the vaccine series at least four weeks) of the anticipated summer onset of pinkeye in your herd, so that cattle will have enough time to mount an effective immune response following vaccination. Depending on the vaccine used, a booster shot 3-4 weeks following the initial vaccine may also be required by the manufacturer; it is a good idea to follow vaccine manufacturer recommendations regarding booster vaccines. Because young animals tend to be most affected, it is critical that they are included in the vaccination program. No single vaccine recommendations work for all herds. If you have not used a pinkeye vaccine before, a reasonable approach is to start by choosing a commercial M. bovis vaccine. If your initial vaccine choice proves ineffective, a variety of options exist including: 1) a different commercial product; 2) an autogenous vaccine, based on eye swabs from infected animals you send in to the lab; or 3) perhaps both. The newest product available on the market (as of 3/2/17) is a Moraxella Bovoculi bacterin from the Addison Biological Laboratory. Dr. Angelos at UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine has been developing an intranasal pinkeye vaccine that might provide better eye immune responses versus traditional subcutaneously injected vaccines.

Dr. John Angelos administers an experimental intranasal pinkeye vaccination at the UC Sierra Foothill Research and Extension Center.

Treatment:

Pinkeye is susceptible to a wide variety of antibiotics; however only two are specifically labelled for the treatment of pinkeye: tulathromycin and oxytetracycline. Other antibiotics are known to be effective, but the use of these drugs for pinkeye treatment is considered “off-label.” Using one of these other drugs should be done under the supervision of your veterinarian. An effective non- antibiotic treatment that might be worth considering is Vetericyn pinkeye spray. Research shows that Vetericyn reduced pain, infection, and healing time of corneal lesions in calves infected with pinkeye. While other treatments such as salt, condensed milk, and dilute povidone iodine have been used by producers, research has not been done on these types of treatments to determine if they are truly effective against pinkeye. Before squirting something in the affected cow or calf's eye, it is always a good idea to ask yourself if you would want that material squirted in your own eye. If your answer is ‘no', it is probably best not to put it in an animal's eye. If ever in doubt, it is always a good idea to consult with your veterinarian for specific treatment recommendations.

Perhaps one of the most difficult aspects of pinkeye treatment is knowing when it is appropriate to use antibiotics. In many instances, eyes that may look like mild or developing pinkeye will heal spontaneously when given time. If you are able to hold the animal for a period of 7-14 days and regularly check the eye, you may choose to withhold antibiotics initially from the animal in order to monitor the eye's progress. This is especially true for animals that have a foreign body (e.g. foxtail) in their eye, which can scratch and irritate the corneal surface around the perimeter of the cornea. Once the foxtail is removed, however, the eye will frequently heal on its own and will not become infected. In many production settings, however, holding an animal for multiple days and/or regularly restraining the animal to inspect the eye is unrealistic, thus an application of antibiotics upon initial identification is appropriate.

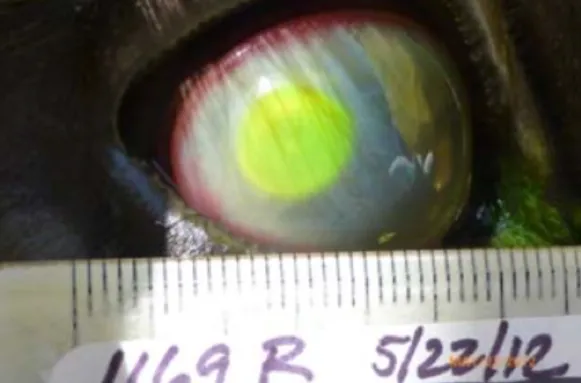

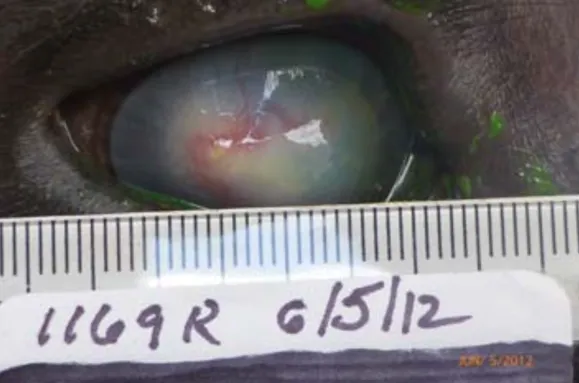

You may also encounter eyes that look like a developing pinkeye, when really they have already begun the healing process. Consider Figure 1, which shows an eye from the same cow on 5/22/12 and 6/5/12. This animal was not treated with antibiotics. The green color is fluorescein, which is a dye that is added to the eye to better identify corneal ulcers associated with pinkeye. On 5/22/12 the animal showed a typical ulcer (area in green); by 6/5/12 the eye had begun to heal. If you came across this animal on 6/5/12 on the ranch, however, you wouldn't have the benefit of knowing the trajectory of the eye's healing process. While antibiotics would not be necessary, it would be difficult to know not to apply them. One important indication that the eye is already healing (and thus does not require antibiotics) is the presence of red blood vessels covering the cloudy part of the eye (see 6/5/12 photo from Figure 1). Other indications that an eye is well on its way to healing and may not need antibiotics is if the eye is not excessively teary or weeping and if the animal is not actively squinting or sensitive to light.

Figure 1.

Some producers will apply an eye patch to a pinkeye-affected eye after they have treated the animal. Using old jeans and tag cement is common. Patches likely provide some comfort to the animal, as it protects the eye from sunlight and potentially dust and flies. Make sure to leave the patch open at the bottom for drainage and air circulation. One important point with patches, however, is that eyes should be checked regularly after applying a patch. Just because you can't see the eye when it's covered by the patch, doesn't mean the eye is doing well. Therefore, make sure you check under the patch frequently to know if the eye is healing or not; checking under a patch ideally a couple of times during the first week after putting it on will help you to know if the eye is improving or not.

All treatment programs should be overseen by your herd veterinarian who can assess the situation and recommend the best prevention and treatment protocol.

Eye stained with fluorescein after removing foxtail. Note ulcer (highlighted in green) on the right edge of the eyeball. Ulcers caused by foxtails or other foreign objects will present on the perimeter of the cornea. This eye healed without the use of antibiotics.