Study calculates cost to ranchers of an expanding wolf population

One wolf can cause up to $162,000 in losses due to reduced growth, pregnancies

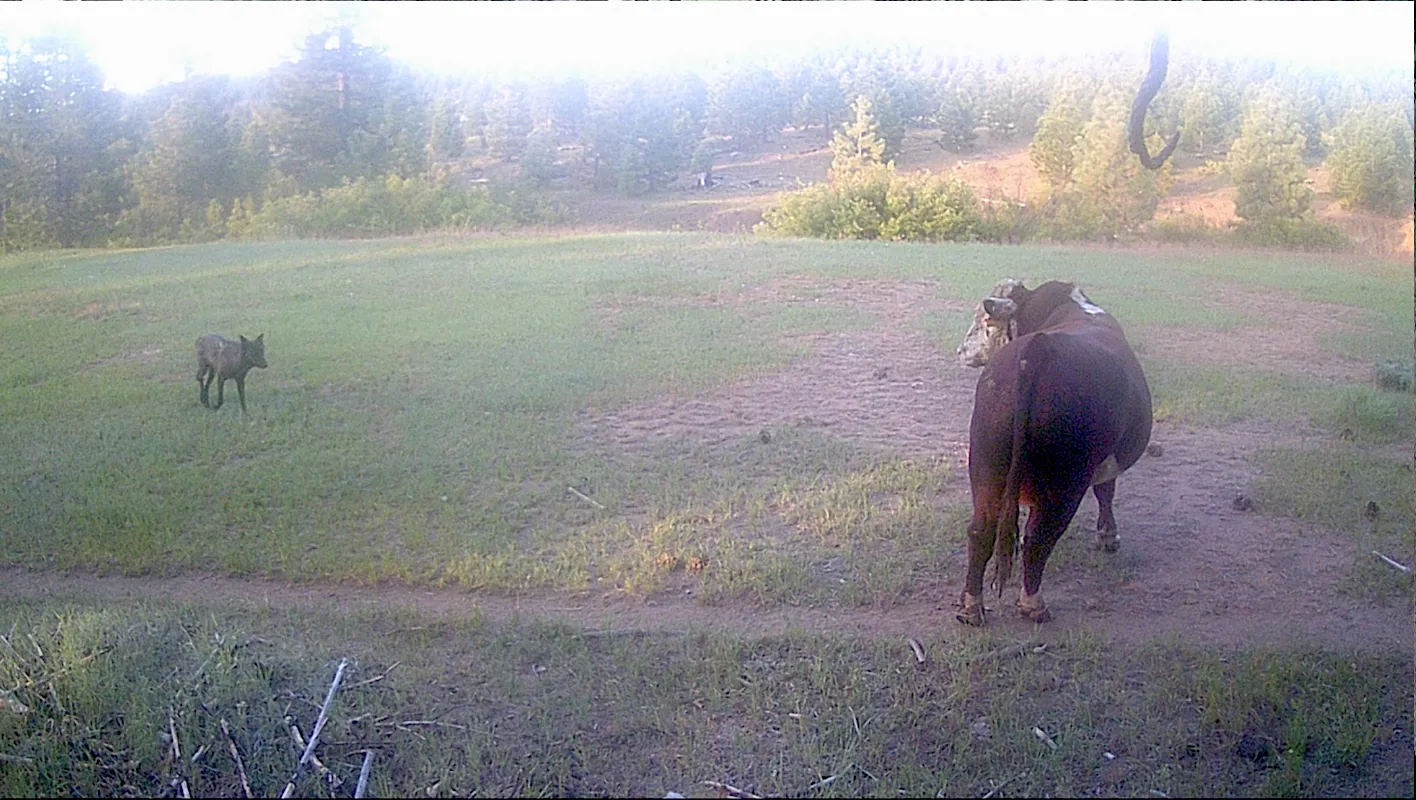

Motion-activated field cameras, GPS collars, wolf scat analysis and cattle tail hair samples are helping University of California, Davis, researchers shed new light on how an expanding and protected gray wolf population is affecting cattle operations, leading to millions of dollars in losses.

Long believed extinct in California, a lone gray wolf was seen entering the Golden State from Oregon in 2011 and a pack was spotted in Siskiyou County in 2015. By the end of 2024, seven wolf packs were documented with evidence of the animals in four other locations. As wolves proliferated, ranchers in those areas feared they would prey on cattle.

Tina Saitone, a University of California, Davis, professor and Cooperative Extension specialist in livestock and rangeland economics, sought to quantify the direct and indirect costs after the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, or CDFW, launched a pilot program to compensate ranchers for wolf-related losses.

“There’s not really any research in the state on the economic consequences of an apex predator interacting with livestock,” she said.

An interdisciplinary team

Saitone proposed the research to her husband, Ken Tate, a UC Davis professor and Cooperative Extension specialist in rangeland sciences. Ben Sacks, director of the Mammalian Ecology and Conservation Unit in the UC Davis Veterinary Genetics Laboratory, joined to analyze wolf scat. Brenda McCowan, a professor of population health and reproduction at UC Davis Veterinary Medicine, examined cortisol levels.

“There’s a lot of nervous ranchers,” Tate said, and “there’s a very limited amount of work on this topic.”

The interdisciplinary research centered on three wolf packs — Harvey, Lassen and Beyem Seyo — and their interactions with rangeland cattle in northeastern California from June to October of 2022, 2023 and 2024. Funding came from the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Western Sustainable Agriculture Research and Extension Program and the Russell L. Rustici Rangeland and Cattle Research Endowment.

The team found that:

- One wolf can cause between $69,000 and $162,000 in direct and indirect losses from lower pregnancy rates in cows and decreased weight gain in calves;

- Total indirect losses are estimated to range from $1.4 million to $3.4 million depending on moderate or severe impacts from wolves across the three packs;

- 72% of wolf scat samples tested during the 2022 and 2023 summer seasons contained cattle DNA; and

- Hair cortisol levels were elevated in cattle that ranged in areas with wolves, indicating an increase in stress.

“It is clear the scale of conflict between wolves and cattle is substantial, expanding and costly to ranchers in terms of animal welfare, animal performance and ranch profitability,” Saitone said. “This is not surprising given that cattle appear to be a major component of wolf diet and the calories drive their conservation success.”

Collaborating for access, information

Researchers trekked into remote rangelands to mount motion-activated game cameras, obtained access agreements from ranchers and permission to put GPS collars on cows. Neither Saitone or Tate had undertaken that kind of work, but years of collaborating on other research paid off, with land managers and ranchers providing information and support.

“This is such a sensitive issue for ranchers and landowners that it took pretty much every bit of my 30 years of network building to get us access to land and cattle for this study,” Tate said.

Local cattle ranchers and others provided tips on locations to post cameras. “Folks on the ground were really helpful in facilitating our understanding of wolf dynamics in general,” he said.

Scanning for wolves

Saitone and Tate deployed a network of more than 120 trail cameras and put GPS collars on 140 cows in locations with and without wolves in their grazing areas. Every two weeks they checked on the trail cameras, swapped out memory cards and cleared away brush or branches that could activate the cameras with just a simple breeze.

The two didn’t know whether they would capture any wolf photos.

“You don’t see these animals very often,” Tate said. “They’re nocturnal. You engage with them almost exclusively via the cameras.”

But one evening reviewing trail camera data, Saitone noticed a herd of cows and calves walking fast and running by a camera for about 30 minutes, followed by two wolves in the middle of the night. “They’d been chasing those cattle and we just caught it on camera,” Tate said. “That stress event just streamed by and, for me, was the first and most exciting finding of evidence wolves were negatively interacting with cattle.”

That wasn’t the end of the discoveries.

Sampling scat

During camera checks, they found canine scat. “Wolves will use roads and trails primarily, just like humans and cattle will,” Saitone said. “It’s the easiest path for them to take so frequently their scat is deposited along the way.”

They began collecting the scat, preserving it with desiccant and handing it over to Sacks for analysis. Of 377 samples they turned over, about 27% were from wolves, with the remainder coming from coyotes, bobcats and lions.

Of the summer 2022 samples, 86% the wolf scat contained cattle DNA and 13 different wolves were identified, all of which had eaten cattle. Over the two years, 72% of the samples had cattle DNA. Mule deer, rodents and occasional bear and bird DNA also showed up in the scat analysis, Sack said.

Sacks emphasized that the data didn’t indicate what killed the cattle, “it just tells us what’s for dinner,” he said.

A new phase of management

Gray wolves are protected under the state and federal law as endangered species. CDFW’s depredation compensation program paid out $3.1 million in initial funding and the agency said April 2 it was moving into a new phase of wolf management given increasing population numbers.

The next phase entails evaluating the status of gray wolves, evaluating potential permits to allow “less-than-lethal harassment” such as noise or use of motorized equipment to deter the predators, an online tool to provide location details of wolves with GPS collars, investigating livestock losses due to depredation and other actions.

Saitone and Tate say the research could better inform the conversation.

“We do need to get toward some kind of coexistence,” Tate said. “We don’t know what that’s going to look like but it doesn’t look like what we’re doing now, that’s for sure. It’s not sustainable. This research helps, I think, to advance that conversation.”

This story was first published on the UC Davis News site.