Why the Milky Way Disappeared from View

Unlike bees, many moths have an obviously fuzzy body. This fuzzy underbelly ingeniously collects pollen from the plant providing the moth with nectar and, as it flies onward, the pollen is then deposited upon the next plant, and so on. While bees tend to forage closer to their nesting location, moths will often travel significant distances navigating by moonlight at a greater height searching for delicately pale leaves and aromatically scented blooms below from which to obtain nectar and indirectly pollinate. This characteristic likely plays a larger role in promoting genetic diversity across plant communities outside the range of diurnal pollinator landscapes. Furthermore, since moths visit such a diverse variety of plant species for nectar, pollination efforts for those plant species also visited by diurnal pollinators see a dramatic increase in overall pollination due to the overlap in the pollinator subgroup efforts. Although the order Lepidoptera encompasses both butterflies and moths, the diversity in the moth world is incredible. Consider the sheer numbers for a moment: there are about 140,000 species of moths versus about 20,000 species of butterflies. Meanwhile, bee species in the United States number a mere 4,000 of the 20,000 species known worldwide.

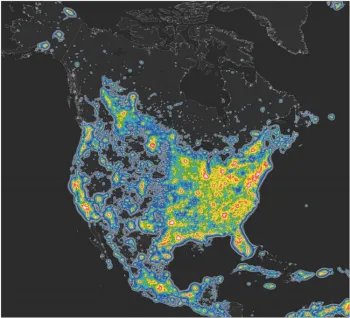

The most recent “world atlas of artificial sky luminance” (published in 2016) found that Singapore was suffering 100% light pollution to the extent that the populace was no longer able to achieve full night vision. The intensity of light pollution at this level has been found to alter circadian rhythms, depress melatonin levels, and increase cortisol levels all of which have profound impacts upon both physical and mental health. The United States contains multiple massive metropolitan areas suffering the same fate and, for more than a decade, it has been demonstrated that 80% of North American citizenry are unable to see the Milky Way. An unintentional consequence of continuous commercial and residential light is the creation of skyglow/light domes which are visible for hundreds of miles. This disruption of darkness necessary for nocturnal animals is not only adversely affecting those heavily populated centers but is resulting in cascading disruption and harm to natural landscapes, agricultural lands and animal life for hundreds of miles. Consider that the light pollution over the Los Angeles basin is visible over 250 miles away in the Mojave Desert. If we use a recent study targeting pollination levels and fruit set alone when light pollution on the blue spectrum is present, we could assume 60% fewer plants being successfully pollinated and 13% lower fruit set for the multitude of Central Valley agricultural fields within 300 miles of Los Angeles or Las Vegas.

Consider entomologist Akito Kawahara's simple message about these essential animals, “We can't live without insects. They are in trouble. ....”. He deftly points to the $70 BILLION estimated U.S. economic contribution these animals make through waste disposal and pollination as a method of demonstrating their vital importance to the world at large. If, indeed, we accept the premise that at least 40% of insect populations are in decline for reasons brought about by human activities, then Kawahara proposes “...people can also be part of the solution” by adopting simple changes with both immediate and long term benefits: -Dim or turn off your lights at night; -Install motion sensors for any essential exterior light sources and save on utility bills; -Use red or amber bulbs which are less attractive to insects; -Mow less and encourage natural habitat and food reservoirs for beneficial insects; -Dedicate 10% yard space to native landscapes to both attract and feed pollinators; -Use insect-friendly soaps and sealants-broad spectrum insecticide kills everything; -Ditch the bug-zappers - science has proven they do not kill predators; and -Become an insect ambassador by learning about all insects in your yard. Dr. Gretchen LeBuhn, an ecologist studying the effects of human induced landscape change on pollinators also suggests getting involved locally. Her “Great Sunflower Project” saw over 60% of participating individuals who found themselves unable to contribute actual data for her research because no insects were available to be counted in their metropolitan area, effecting at least one change to their immediate landscape in an effort to attract both diurnal and nocturnal pollinators back to their communities.

Although light pollution has not found its way into mainstream focus by governing bodies worldwide, scientific inquiry and investigative focus have shifted strongly in the past decade to spotlight it as a threat that could be substantially reversed if given the proper attention. Many scientists across multiple disciplines are turning to public involvement in hopes of turning the tide back in favor of co-existence with the animals necessary to human existence.